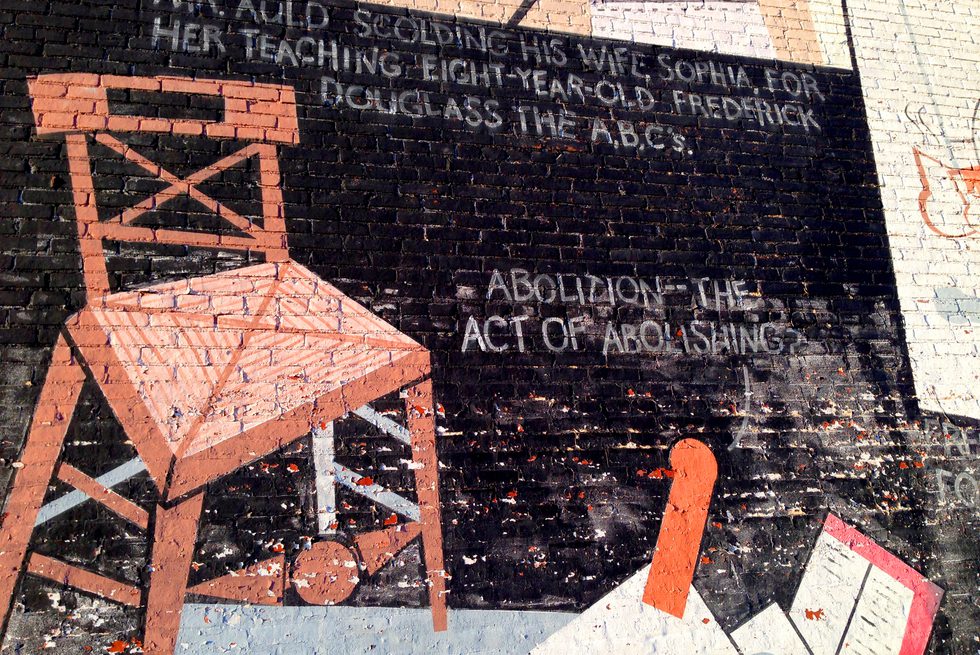

Care, Community, and Commitment in the Abolitionist Classroom

From the Series: Abolitionist Pedagogies

From the Series: Abolitionist Pedagogies

Prisons exist specifically to separate and isolate people from society and their communities. The impact of such separation is deepened by punitive stigmatization, fear-mongering, racism, barriers to communication with the outside, and a lack of accountability or transparency about what is happening inside. State-sanctioned disappearances (of people into prisons and prisoners into solitary confinement), tight control on information, a normalized culture of dehumanization and brutality, staff impunity, and a political commitment to the view that prisons are necessary responses to harm all contribute to a sense of carceral inevitability and the uselessness of resistance.

An abolitionist anthropology pedagogy prepared to confront and contest these realities thus must incorporate critical approaches that do many things simultaneously: reveal and attack the supremacist, racist, and colonial roots of the contemporary prison industry and master narratives about the need for prisons; model alternative forms of community building through creating classroom and community cultures of radical care and belonging; build bridges of communication outside of state surveillance that span prison walls; demonstrate the possibilities of alternative ways of responding to harm; and open supportive spaces for incarcerated scholars to pursue and share research of their own design.

Maine has been an interesting place to pursue these aims. Over the past five years, the Maine Department of Corrections (MDOC) has experimented with expanding higher education and scholarship opportunities for people in prison in collaboration with outside colleges and community groups. The impact of the COVID epidemic, a significant Mellon grant to the University of Maine at Augusta that supported technology investments, and support from leadership in Maine’s Department of Corrections provided openings for extending internet access inside Maine’s prison facilities, which now provide Wi-Fi on a limited and hierarchical basis to adult students incarcerated in all Maine prisons. As internet access and a more progressive attitude toward communication across prison walls expanded, new opportunities for liberatory education based in abolitionist pedagogies became possible.

This post focuses on Colby College’s higher education in prison program, one of a number of efforts over the past five years in Maine to build community across prison walls based in a praxis of liberatory co-learning and abolitionist commitments to transformative justice.[1]

Colby College is a small liberal arts school which only offers undergraduate degrees in the liberal arts. During 2021-23, we offered an “Across the Walls” program with two formats: 1) specially designed and designated courses in which incarcerated students could enroll, at no cost, alongside students on campus; and 2) courses taught by incarcerated professors. CATW courses ensured that incarcerated students comprised one-half to one-third of each CATW class, except for CATW courses taught by incarcerated faculty members, who are not allowed by MDOC policy to teach incarcerated students.

The CATW model was explicitly rooted in abolitionist pedagogy (Castro and Brawn 2017; Love 2019; Rodriguez 2010). The CATW mission statement reads:

In collaborative classrooms across prison and college walls, Colby Across the Walls (CATW) aims to build community by creating spaces of intellectual freedom and emotional flourishing. CATW does this primarily through offering courses that include students and faculty based on the Colby campus and students and faculty incarcerated in Maine’s prisons. Our courses balance inside and outside students, open teaching opportunities to inside scholars, bridge our siloed spaces of residence, and build intellectual relationships based on dignity, mutual respect, and a commitment to shared learning. CATW courses will be held in person at least eight times during the semester. CATW courses are content-rich, based in emancipatory pedagogies, and dedicated to building strong multifaceted relationships, nurturing individual voice and self-awareness, cultivating active listening, and building trust. CATW seeks to open collaborative spaces where creative work can emerge, new imaginaries can form, and shared ethical visions can take shape.

Following Bettina Love, the CATW program grew from an abolitionist pedagogy which required an explicitly political stance by the faculty: “Abolitionist teaching is choosing to engage in the struggle for educational justice knowing that you have the ability and human right to refuse oppression and refuse to oppress others, mainly your students” (2019, 11). To do this in college classes which included incarcerated students, we began with an open conversation with currently incarcerated students about their priorities. As Robert Scott advises, “we must learn how to hear the students’ articulation of what is needed. We have to embrace the students’ interests where they are, and listen to what they need to get somewhere with their work” (2013, 29). Their advice included the following instructions.

Please do not assume the following:

Building on this foundation, the CATW program developed the following expectations:

We also held campus-wide meetings to explain CATW pedagogy and provide resources to faculty and students interested in abolitionist pedagogy, developed a liberatory education guide for faculty from other colleges and universities who taught courses inside prisons, offered CATW versions of Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, and opened discussions on campus about expanding DEI initiatives to include those who are justice-impacted.

It is important to note that many of these practices depart from the national standard for “inside-out” classes. Many prison education programs do not treat incarcerated students in the class as fully enrolled college students on the home campus who are provided with campus student IDs, email accounts, and access to campus resources; do not allow communication via email and Zoom outside of class time between faculty and incarcerated students, between incarcerated and non-incarcerated classmates, or between incarcerated students at different prisons; and mandate that communication between faculty and incarcerated students cease immediately upon the conclusion of the semester. Some do not even provide college credit from the college offering the class (MIT, for example, offers classes in Maine prisons but will not offer incarcerated students MIT college credit. Rather, incarcerated students who take MIT classes receive credit for their MIT class from a local community college.) Additionally, Colby’s willingness to employ a faculty member who was incarcerated in the state’s maximum-security prison (and another while he was on home confinement after being released from prison) was pathbreaking nationwide (see Field 2023). Negotiating for this administrative and bureaucratic structure required buy-in from both campus and MDOC leadership, and we recognize that much of what we were able to do was unprecedented elsewhere and utterly dependent on the consent and support of the top administrators at each institution.

CATW classes typically involved several components and practices of abolitionist pedagogy:

During 2022-23, CATW classes were accompanied by an Abolitionist Pedagogy conversation series that met once a month on Zoom with a guest speaker. The series kicked off with a panel of three incarcerated scholars pursuing graduate work who established the primary questions about the praxis of liberatory education in carceral settings. Incarcerated scholars Zoomed into the meetings every month for free-flowing, unsurveilled discussion.

CATW only ran for 4 semesters before being suspended when the director (Besteman) was suspended by MDOC (although currently CATW is being retooled for a project by an organization called Reentry Sisters which supports women in reentry to complete their college degrees). The opportunities that had opened in 2021 to allow CATW to adhere to principles of liberatory education and abolitionist pedagogy have since narrowed dramatically with the departure of the MDOC administrator most supportive of these efforts. Access to the internet for incarcerated scholars has been severely reduced and the control of internet access has become a tool of punishment, with incarcerated scholars routinely losing access to the internet for lengthy periods of time. Currently most college classes are entirely online and many are asynchronous, which destroys any efforts toward classroom-based community building and mutual care. The ability of incarcerated scholars to Zoom with their professors and classmates, or to join professional lecture series or conferences, has been severely curtailed, and professors found in violation or who are accused of becoming too close to their students are suspended or have their classes cancelled. A much tighter structure of surveillance now monitors what incarcerated scholars are communicating to people on the outside. In short, the dramatic curtailments seem to reflect a general feeling amongst DOC staff that internet access had become far too permissive, and that, despite secure firewalls which greatly constrained what incarcerated internet users could access online, incarcerated scholars were accessing the internet for purposes not linked tightly enough to their educational programs.

On the positive side, the CATW approach created relationships that continued beyond the demise of the program. Some students who have been released now work on projects with their former professors, and some former students still keep in touch with their incarcerated professor. The campus was introduced to the normalized presence of incarcerated scholars as fellow Colby students and faculty, which precipitated campus-wide conversations about what responses to harm based in restorative justice rather than punitive carcerality could look like. The program opened the possibility of employment for incarcerated professionals at free world wages with outside employers. And CATW can still stand as an aspiration to the possibility of liberatory education inside prisons in collaboration with college campuses.

But there is a cautionary tale here. Abolitionist pedagogy inside prison spaces is profoundly fraught and, I believe, seldom sustainable unless top corrections administrators demand compliance from lower-level staff, many of whom, it seems, object to prisoners even having access to college classes. Because access to education inside prisons is a privilege and not a right, college classes can become weaponized spaces, with access used to reward and punish those perceived as committing infractions. That does not mean faculty on the outside should give in to carceral logics in order to sustain higher education in prison programs; it just means we have to fight harder.

[1] Some other efforts included a Justice Think Tank for incarcerated scholars who received compensation for their policy research from the Alliance for Higher Education in Prison and a public humanities initiative called Freedom & Captivity (see also Small 2024), which trained inside facilitators to teach community classes to outside groups about incarceration, liberation, and transformative justice.

Castro, Erin L. and Michael Brawn. 2017. “Critiquing Critical Pedagogies Inside the Prison Classroom: A Dialogue Between Student and Teacher.” Harvard Education Review 87, no. 1, 99–121.

Field, Kelly. 2023. “Lessons in Imprisonment. Students at Colby College Learn from an Expert: A Man Serving Fifty Years.” Chronicle of Higher Education, May 2.

hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge.

Jones III, Arlando ‘Tray.’ 2014. “Prison from the Mind of a Prisoner.” In Philosophy Imprisoned: The Love of Wisdom in the Age of Mass Incarceration, edited by Sarah Tyson and Joshua M. Hall, 129–142. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Love, Bettina. 2019. We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Boston: Beacon Press.

Novek, Eleanor. 2019. “Making Meaning: Reflections on the Act of Teaching in Prison.” Review of Communication 19, no. 1: 55–68.

Rodriguez, Dylan. 2010. “The Disorientation of the Teaching Act: Abolition as Pedagogical Position.” The Radical Teacher 88: 7–19.

Rosas, Desiree, George Villa, and Megan Raschig. 2024. “Circling Up—In the Classroom.” Teaching Tools, Fieldsights, September 3.

Scott, Robert. 2013. “Distinguishing Radical Teaching from Merely Having Intense Experiences While Teaching in Prison.” Radical Teacher 95: 22–32.

Small, Linda. 2024. “The Freedom & Captivity Curriculum Project.” In Higher Education and the Carceral State, edited by Annie Buckley, 31–41. New York: Routledge.