Many of us are producing and teaching ethnographic work that is nonlinear, multimodal, multisensorial, and/or born digital. Students are energized when they encounter these newer forms of “producing ethnography” and many are thrilled at the chance to produce their own projects in these creative forms. I regularly teach a range of courses that place a strong emphasis on experimental forms of ethnography and questions of craft and epistemology. Courses include: “Experimental Ethnography,” “Ethnography and Its Edges,” and “Fieldwork into Performance.” In this post, I share my approach to teaching, specifically in terms of design thinking, epistemological stakes, and transduction pedagogy.

A number of pedagogical goals frame my courses. They provide guidelines for inquiry, production, and evaluation. Goals on syllabi include:

- Understand the motivations for contemporary interventions related to experimental ethnography and multimodal, multisensorial knowledge production.

- Learn how anthropological theory, insights, data, and analysis can be expressed in a range of different genres, e.g. graphic novels, installations, poetry, theater, performance, mixtapes, sonic ethnography, and creative nonfiction.

- Interrogate and assess epistemological implications of choices in scholarly form and design.

- Understand and apply concepts of genre, affordances, and form-meaning relations. This includes learning genre-specific technical vocabulary to identify features of form, structure, and design.

- Analyze how form, structure, and design create possibilities for communicating anthropological theory and ethnographic meanings.

- Experiment with different forms of ethnographic communication/knowledge production.

Cultivating design thinking and attention to the affordances of genre and medium requires a lot of scaffolding. That said, many students already have excellent design sensibilities, without technical vocabulary for craft and affordances. Many are prolific social media content creators and most are voracious consumers of a vast range of multimodal forms in their personal lives. Bringing these interests and sensibilities into an academic context and “muscling up” with technical vocabulary and attention to epistemological stakes is energizing and empowering for them.

For scaffolding, I use short assignments, structured to invite students to experiment with form and to write process notes about how they arrived at specific representational and design choices. We usually start with rudimentary semiotics, for example noticing how choices of colors can evoke connections to moods and settings, and how font choices such as bold or ALL CAPS can communicate urgency or emphasis. Vidali 2023 provides an explicit discussion of how to develop and articulate design sensibilities with simple exercises focused on these familiar kinds of form-meaning relations. I also like to jump-start conversations around design choices by unpacking memes (see Figure 1) during class discussion. I point out that students can easily zero in on design elements and decode meanings... and that they routinely do this. I then model how they can go in the opposite direction: first identifying a concept and then encoding it in a form.

For highlighting epistemological stakes and the range of types of creative forms for ethnographic communication, I use Varzi (2018) and Vidali (2016) as orienting polemics.[1] Importantly both essays engage questions of how and why experimental forms of anthropological knowledge production have until recently been kept on the margins of anthropology, and even viewed as “dangerous” and “unserious” forms of scholarship (see cover image). Varzi raises the stakes around genre choices, stating that “ethnographic data wants and needs a certain form.” This yields many productive questions for students to engage, for example: Is ethnographic evidence more compelling and less mediated if the original form is used? Do ethnographies about sounds, for example, need to be produced in sonic forms? Are person-centered ethnographies of emotional dilemmas best conveyed through graphic novels that use extreme close-ups of faces? And/or thought bubbles for text representing inner thoughts?

When it comes to engaging specific ethnographies, I assign scholarship that includes statements that unpack the backstory of craft and the ways that theory and findings are amplified via form. By reading authors’ direct reflections on their form and design choices, students learn both design thinking and how ethnographers justify their design thinking processes. Redmond and Phillips (2017) and the Appendix in Hamdy et al. (2017) and are excellent examples of this.

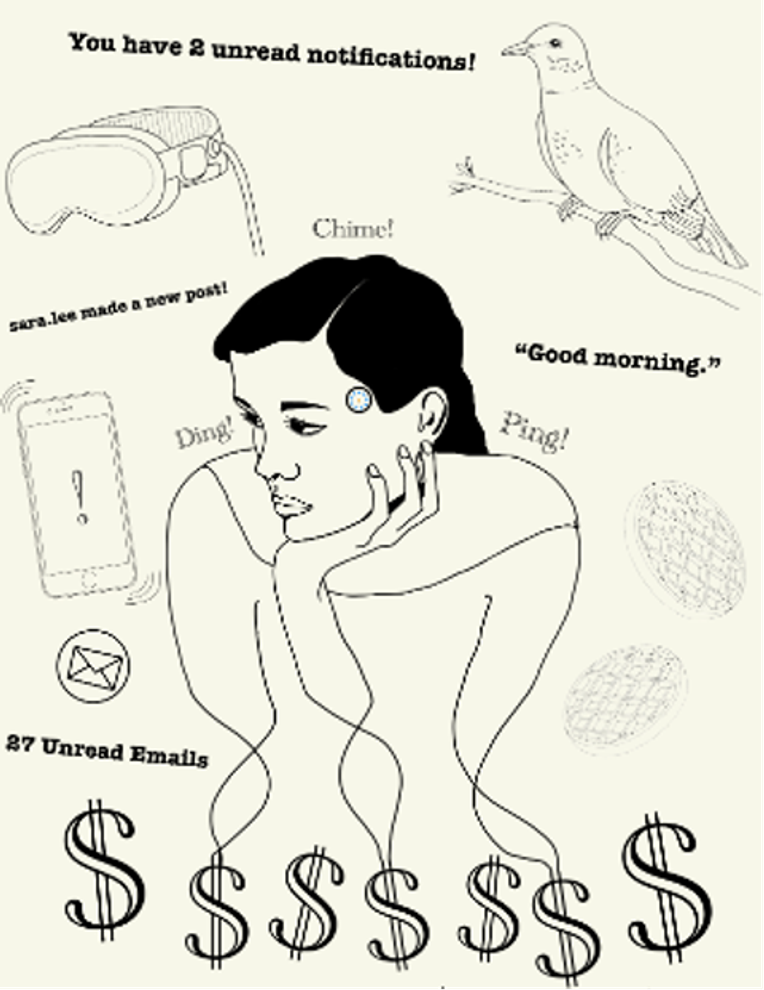

Hamdy et al.’s use of splash pages and ethnographic representations of street art in Cairo inspired me to think more broadly about how public muralists and graffiti artists also use ethnographic sensibilities. Based on this, I built an exercise to guide students to represent ethnographic insights through drawings and mural sketches, and write rationales for their design choices (Vidali 2024).[2] For example, this spring semester Alyssa Jean-Louis created a dynamic mural sketch based on ethnographic research, to convey feelings of technological overload when waking up in the morning (see Figure 2). Weary attention is drawn to the left, a chaotic and busy space of technological noises, notifications, and vibrations, while sounds of the mourning dove and even the taste of freshly toasted waffles are barely noticed, let alone enjoyed. Worry and exhaustion sink in, even in the morning, as the day starts within a system undergirded by the driving force of profit.

For major research projects, students are required to write a short accompanying essay that engages prompts such as these:

- Choice of Form: Why did you choose the form that you did? How/why is this form uniquely suited to convey the findings and respond to the research’s burning issues?

- Process/Craft: In moving from data to a crafted project, what affordances of form are you using/activating? What design choices did you make? How do these choices support your ethnographic material & your goals? What was the process like in crafting your ethnographic project? What did you experience?

Again, the pedagogical challenge is not just to encourage students to experiment with different forms and be creative, but to also guide them in being accountable for their choices.

Every semester, I also create one or two assignments that involve transduction, understood as the conversion of ethnographic insights from one genre into another genre.[3] In transduction exercises, students read a graphic novel, for example, and then use a different form such as a poem, to convey some of the same voices, stories and ethnographic insights that are represented in the graphic novel. Or they read an ethnography, and then construct a mixtape to convey the same key insights or themes that are focal points in the written ethnography. Below are some sample exercises.

Transduction Practice: Poem to Graphic

Part 1: Select one poem from Rosaldo (2013). Create a one page graphic comic that conveys the same ethnographic insights, emotions, experiences, and events. Use techniques we have discussed in class with respect to Hamdy et al. (2017).

Note: You don’t need to put all the words of the poem into words in the comic. Don’t worry about drawing skills, you can use stick figures, or clip art, or gifs, or some form of doodling to create your images and panels.

Part 2: Write process notes that include:

- Title and page number of the poem from Rosaldo.

- Key ethnographic insights, emotions, experiences, and events that are conveyed in the poem.

- Discussion of your graphic comic design choices, e.g.: Panel 1 is an extreme close up of Manny’s face. This conveys intensity. Panel 3 is a splash panel with sound effect words that bleed down to the bottom of page. This is used to convey the soundscape of village life.

Transduction Practice: Graphic to Poem

Part 1: Select one character from Hamdy et al.’s Lissa. Using Rosaldo (2013) as an inspiration, write a 125-150 word poem using your selected character’s first-person perspective. Create a poem that highlights the social embeddedness of this character’s relations to health and medicine, as per the argument in Lissa.

Part 2: Write process notes that include:

- Name of character from Lissa

- Key ethnographic insights, emotions, experiences, and events related to this character that you are using to inspire your poem. Include page numbers.

The benefit of these transduction exercises is twofold: Firstly, they allow students to more deeply evaluate the power and affordances of specific forms and the possibility that two different mediums are differently suited for expressing the “same” content. Is the poem better or is the comic better? What are the pros and cons of each? Secondly, they give students a chance to explore their own strengths in diverse genres, and see which is the most promising and exciting for developing their course research project.

Supporting students to produce ethnography through creative forms also means supporting them to share their work—with each other and with wider audiences. All too often students produce coursework that is seen by the professor only, and that is often produced and submitted just before a deadline. I build studio time into my classes for students to work on projects in the classroom. We have low-stakes workshops to share work in progress. At the end of the semester we have showcase events and flash presentations (see below). In addition, students sometimes create blogs or Instagram accounts to share multimodal projects, and we often use the display cases in our department hallways to feature creative projects. These are all ways to share and celebrate work, be accountable for it, and develop teamwork, presentation, and public speaking skills that extend beyond the course.

Left to right: Akash Sathiyamurthi, Vinay Devulapalli, Karthik Valiveti, and Ann Liu. Photograph by Debra Vidali and shared with permission.

Footnotes

[1] In advanced classes we also read Dattatreyan and Marrero‐Guillamón (2019), Collins et al. (2017), and Pink (2011), among others, for disciplinary foundations and overview statements.

[2] See Cahnmann-Taylor and Jacobsen (2024), an extraordinary new work with detailed examples of exercises and tools for rending ethnography into poetry, music, performing arts, visual media, and more.

[3] Marcus offers this quote from Webster’s Third New International Dictionary at the beginning of his foreword to Hamdy et al. (2017): “Transduction: the action or process of converting something, and especially energy or a message, into another form” (11). A much earlier and longstanding use of the term “transduction” can be found in semiotic approaches (see Kress 1997).

References

Cahnmann-Taylor, Melisa and Kristina Jacobsen, eds. 2024.The Creative Ethnographer’s Notebook. New York: Routledge.

Collins, Samuel Gerald, Matthew Durington, and Harjant S. Gill. 2017. “Multimodality: An Invitation.” American Anthropologist 119, no. 1: 142–146.

Dattatreyan, Ethiraj Gabriel and Isaac Marrero‐Guillamón. 2019. “Introduction: Multimodal Anthropology and the Politics of Invention.” American Anthropologist 121, no. 1: 220–228.

Hamdy, Sherine, Coleman Nye, Sarula Bao, and Caroline Brewer. 2017. Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Kress, Gunther. 1997. Before Writing: Rethinking the Paths to Literacy. New York: Routledge.

Marcus, George. 2017. “Foreword: Lissa and the Transduction of Ethnography.” In Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution, edited by Sherine Hamdy, Coleman Nye, Sarula Bao, and Caroline Brewer, 111–14. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Pink, Sarah. 2011. “Multimodality, Multisensoriality and Ethnographic Knowing: Social Semiotics and the Phenomenology of Perception.” Qualitative Research 11, no. 3: 261–276.

Redmond, Shana L. and Kwame M. Phillips. 2017. “‘The People Who Keep on Going’: A Listening Party, Vol. I.” In Futures of Black Radicalism, edited by Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin, 206–224. New York: Verso.

Rosaldo, Renato. 2013. The Day of Shelly’s Death: The Poetry and Ethnography of Grief. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Varzi, Roxanne. 2018. “The Knot in the Wood: The Call to Multimodal Anthropology.” American Anthropologist website, June 5.

Vidali, Debra. 2016. “Multisensorial Anthropology: A Retrofit Cracking Open of the Field.” American Anthropologist 118, no. 2: 395–400.

———. 2023. “Developing Design Sensibilities.” In Print Politics, published by the collective for Multimodal Makers, Publishers, Collaborators, and Teachers (CoMMPCT).

———. 2024. “Representing Ethnographic Insights through Mural Sketches.” In The Creative Ethnographer’s Notebook, edited by Melisa Cahnmann-Taylor and Kristina Jacobsen, 162–168. New York: Routledge.