This post is part of a two-post series on teaching with the work of Edward Said. Read the epilogue here.

Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) has profoundly affected our teaching and research, as it engages with fundamental historical questions that continue to be relevant for, and resonate with, contemporary global shifts in politics and culture. This work was particularly inspirational and central to the design of our co-taught course, Constructing the Other: Orientalism Across Time and Space.

We (Katherine and Girish) returned to Said’s book Orientalism around 2015, in a time of change and flux, when post-2011 events such as the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, and Black Lives Matter raised questions about the future and the role that unfreedom and colonial-capitalism played in these unfolding events. These questions, pertaining to coloniality (Quijano 2000) and othering, also spoke to our different lived experiences, the lands we worked and lived in, and our personal backgrounds. We found many relevant connections (historically and socially) to the presence of coloniality in our lives, in our disciplines, and to the places we have conducted research. Katherine is an ancient historian who works on Egypt and is a 12th-generation French settler from Québec (former French colony, later colonized by the British Crown). Girish is an anthropologist, part of a Sindhi diaspora (which emerged due to British colonialism and the Partition of India and Pakistan), and is from Singapore. British colonialism and settler colonialism have profoundly impacted our self-identities and the ways in which we approach our work and teaching.

How are we (un)learning?

Constructing the Other is cross listed in Anthropology [ANT], History [HIS], and Classical Studies [CLA]. We have taught this course three times so far. We conceived the course so that it is a truly co-taught one: Weekly readings and other preparatory material include a balanced selection of CLA/HIS and ANT-related works (readings, but also podcasts, videos, archival material, and art pieces), and we actively prepare and teach each class together.

Our students are undergraduates at the Scarborough campus of the University of Toronto (UTSC). For context: UTSC has more than 14,000 students, the majority of whom are racialized and belong to the Global Majority (regions people recognize as East Asia, West Asia, South Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America). This demographic is in sharp contrast with the St. George (downtown) campus, which is less diverse and whose links to the country’s colonial past are more explicitly displayed. Another defining feature of UTSC is that many of its domestic students live in low- to middle-income neighborhoods, often relatively close to the campus. Many of the questions discussed in our course, such as the impacts of colonialism, postcolonialism, capitalism, racism, fascism, and genocide, are not abstract components of theories about the world but intrinsic parts of the worlds that many of our students (and their ancestors) come from. There is nothing “post” colonial about the global contemporary (Madiou 2021; Blouin and Akrigg 2024), and our students arrive to class with an acute knowledge, and experience, of that fact.

“What brings anthropology and ancient history together?” This is what some university bureaucrats asked us when approving the course. It will not be news to anyone that many academic disciplines were born in Europe during the Age of Empires. It is certainly the case of classics, archaeology, and other antiquity-related specialities. It is, also, the case of anthropology. While the degree to which these disciplines have decolonized themselves varies greatly, they often do so in relative isolation from each other. Our course aims to critically examine the colonial baggage we continue to carry—a reality which has deep implications in the ways in which knowledge is constructed, and academia (re)produces itself.

Orientalism 101

In this course the concept of Orientalism is central to each week’s class. We also make it a point to have our students end the course having carefully read and processed all of Said’s Orientalism.

Starting from a careful reading of this book and of the scholarly and popular responses it has led to, Constructing the Other reflects on the many ways in which Orientalism has continuing relevance in the racist, gendered, and classist stereotypes we encounter in postcolonial and settler colonial countries, social and legacy media, government policies, and university settings. When curating the weekly preparatory material for each of the three iterations of Constructing the Other, we started from the premise that this course ought to be informed by an interdisciplinary teaching methodology and processes of unlearning. How can we further such conversations better in the classroom? And how can we do so in a way that fosters a constructive degree of transdisciplinary learning and reflection?

It is also essential for us to acknowledge the connection between the writing of Said’s Orientalism and the work of Malaysian scholar Syed Hussein Alatas ([1977] 1997). Alatas’s book The Myth of the Lazy Native: A Study of the Image of the Malays, Filipinos and Javanese from the 16th to the 20th Century and Its Function in the Ideology of Colonial Capitalism, predates Said’s Orientalism by one year and speaks to the role of myths in colonial ideology and of extractive capitalism in this Asian setting. In Orientalism Said also discusses the role of myths in ideology and institution building (1978, 321):

Mythic language is discourse, that is, it cannot be anything but systematic; one does not really make discourse at will, or statements in it, without first belonging—in some cases unconsciously, but at any rate involuntarily—to the ideology and the institutions that guarantee its existence.

Both Alatas and Said used history, historical texts, and case studies to reveal sociological processes of othering and the ongoing influence of negative stereotypes.

Throughout the term, we purposely engage with Orientalism in both a literal (the “Orient”) and a paradigmatic (“the Other”) way. This allowed us to expose students to a variety of geographical contexts, temporalities, and source materials, and, crucially, gave them the opportunity to make transnational and diachronic connections. Indeed, over the years, our class included analysis of art and popular culture, of historical and literary texts, and of readings from regions that include Turtle Island, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, Ireland, India, Ghana, South Africa, and Singapore.

Where are we (un)learning from?

It is essential for us to start the term by situating ourselves as a group, and the (un)learning journey we were embarking on, on the land our university stands on. For this reason, after two classes entitled “Orientalism 101” and “The Age of Empires: Understanding ‘Us’ and the ‘Other,’ ” we dedicate a module (three to four classes) to the exploration of the relationship between Orientalism, classics, and White settler colonialism in Ireland, North America, Oceania, and Palestine (Allen 2012; Yuzwa 2021; Tuhiwai Smith 2021; Blouin 2023; Sabbagh-Khoury 2023), as well as to Indigenous refusal, resistance, and resurgence (Simpson 2014; Maracle 2015; Spice 2016). Our approach to in-class learning was also inspired by Indigenous pedagogies. For instance, we endeavoured to have in-class discussions reflect a circle. As we explicitly told our students at the start of term, this format is inspired by the talking circle mode of learning, which the Stó:lō writer Lee Maracle introduced us to back in 2018 (also cited in Barkaskas and Gladwin 2021). In our syllabus, we cite our colleague Karina Vernon’s definition of the talking circle (personal communication):

Talking circles symbolize completeness and equality. All circle participants’ views must be respected and listened to. All comments directly address the question or the issue, not the comments another person has made. Going around the circle systematically gives everyone the opportunity to participate. Silence is also acceptable—any participant can choose not to speak.

We asked students to start their circle sharing with the prompt we learned from Lee Maracle: “I was struck by….” This prompt, as well as the circle format, allows for more attention to be paid to each member of the group as they are sharing thoughts and feelings about the week’s readings. It also fosters trust, active listening, and non-hierarchical ways of learning, and normalizes the embodied, and emotive, processing of knowledge that remains too often shunned upon in Eurocentric academia. During our in-class circle, students speak one after the other without us intervening. Once everyone has spoken, we invite anyone who wants to add something to do so. We conclude the circle by bringing together all the threads the students have woven together throughout the circle.

Students’ responses to the circle tend to be the same every year: At first, they are unsettled by the fact that they see and are seen by each other. While sitting in a circle, one cannot hide behind a screen or tune out as easily. We encourage students to take note of how this setup makes them feel and to embrace and sit with their discomfort. Very quickly, the discomfort turns into trust, and students prove more engaged and thoughtful than in traditional, more hierarchical, classroom settings.

We teach our students that the Land is a historical actor; one that encompasses a wide array of past and present beings; one where power is negotiated, enforced, and contested, in a multitude of messy, and uncanny, ways. One reading by Stó:lō writer and poet Lee Maracle (2015, 53) emphasized how “violence to earth and violence between humans are connected.” In her book Memory Serves, Maracle (2015) writes about the suicide of sockeye salmon in British Columbia and how such unexplainable events are connected to and have coincided with specific human tragedies including the murder of Indigenous women in Canada. In 2020, we organized a teach-in to better understand the legal and colonial nuances of a pipeline that was scheduled to be built through Wet’suwet’en territories. In class, we had spoken about anti-colonial resistance, the use of law to keep people tied to colonial systems of slavery and capitalist dependence, as well as the international solidarity movements that encompassed both colonizers and colonized peoples. We learnt so much from our Indigenous colleagues and experts about how legal documents around ownership of land had been conjured and used against Indigenous peoples, how court battles had been fought and won, and the ongoing resistance and solidarity that is necessary in making sure that Canadians do not forget their own checkered history of colonialism that still allows for corporate acts of theft.

What else are we (un)learning?

After situating the course within Said’s work and anchoring our collective pedagogical journey on the land on which it takes place, we opt for a selection of thematic classes, which we update each time we teach the course according to current geopolitical developments and broader societal conversations. In the last iteration of the course (winter 2025), we opted for the following themes: Orientalism and the media; the politics of heritage in Egypt; classics, archaeology, the antiquities trade, and museums; and digital Orientalism and genocide. Having benefitted from reading Said’s Orientalism at the start of term and having reflected on how it also speaks to other forms of othering, including on Turtle Island, students come to these thematic classes prepared to ask questions about power, racial and gendered violence, elite capture, the administrative management of populations and capitalist exploitation of environments, Indigenous and anti-colonial resistance, and the ways in which Orientalism continues to manifest in contemporary postcolonial and settler colonial politics from Turtle Island to West Asia, from South Asia to Southeast Asia.

Throughout the term, we encourage students to ask questions like: “What is occluded?” (in the readings, the texts, the images, the political narratives) and “Who has the permission to narrate?”

In order to help students understand how Orientalism (and its flexible mechanisms of othering) remains relevant in our collective stories and histories, we share archival material, colonial documents, documentaries, as well as contemporary popular culture media (music videos, clips from movies, ads) with our students in every class.

Each week, we dedicate a segment of the class to a case study, which is meant to allow students to put their (un)learning in practice. Each case study corresponds to a particular, primary evidence (a text, an image, a video, a work of art, a media output) that pertains to the week’s topic and preparatory material. After reading/listening to/watching said evidence, students are asked to unpack its meanings and subtext in small groups. We then gather together and discuss each group’s findings. Four such case studies have proved particularly impactful to all three groups who took the course so far:

1. The Indian Act

We assigned Canada’s “Indian Act” (first introduced in 1876, with a new version passed in 1951) as part of the weekly material and discussed its content in class. Although this is a foundational text when it comes to settler colonial rule in Canada, the overwhelming majority of the students had never read it. We learned more about its continuing relevance for the dehumanization and genocide of Indigenous lives in Canada and the ongoing dispossession and marginalization of Indigenous peoples.

2. Kuchuk Hanem

Together with the Description de l’Égypte frontispiece page, the passages of French writer Gustave Flaubert’s travel memoir dedicated to Kuchuk Hanem is the Orientalist source that was the most impactful on the students. In all three iterations of Constructing the Other, our students were quick to spot the colonial, misogynistic, and infantilizing tropes in Flaubert’s description and to compare this with other classic stereotypes of powerful women like Cleopatra VII, Matoaka (most often known as ‘Pocahontas’), and Sarah Baartman, whose ancient and modern Orientalizing renderings we also discussed during the course of the term.

3. Description de l’Égypte’s Frontispiece Page

The in-class autopsy of the Description de l’Égypte’s frontispice page helped us explain so much about the relationship of European imperialism, including the colonial entanglements of our fields, with Egypt and, more broadly, West Asia. This enframed (Mitchell 1988), compacted, antiquarian, quasi-lifeless rendering of Egypt acts as a visual rendition of both the discursive entailments of Orientalism and their function within modern notions of “civilization” and Whiteness (Blouin 2018). The plate is so rich in details that it easily fills up one hour of discussion.

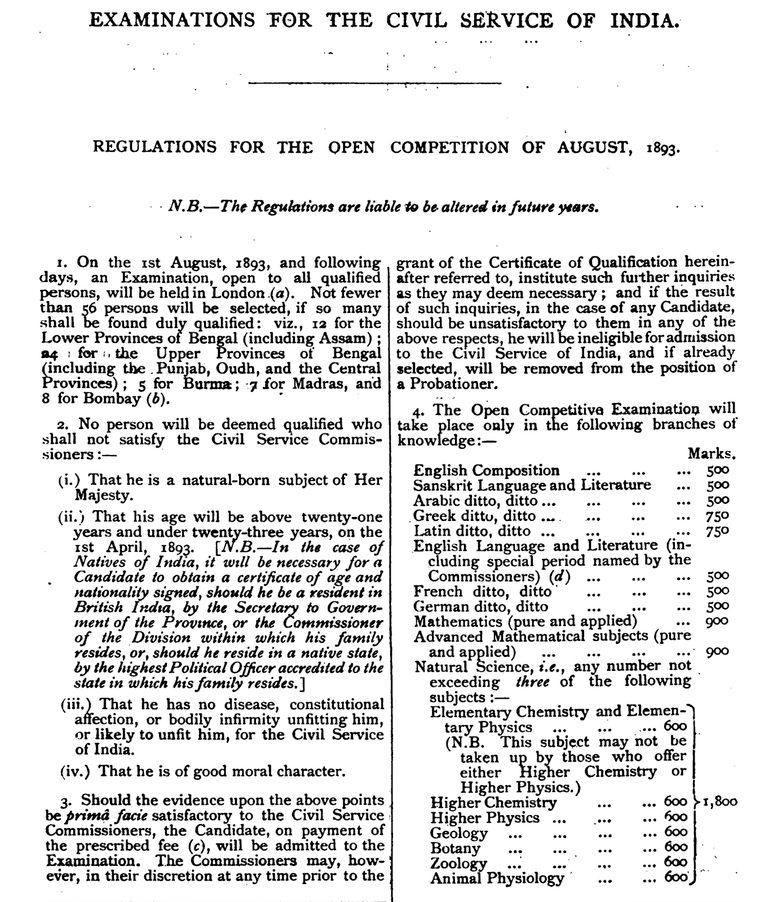

4. 1893 British Civil Service Examinations in Colonial India

In another class we discussed the list of requirements to qualify for the 1893 British Civil Service Examinations for colonial India. Apart from the stringent language requirements (which included Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, and Arabic), “horse-back riding” skills and the ability to travel to London for the exam were points of exclusion in what was touted as an exam aimed to include “Indians” (“Hindus and Mohamedens”) into the British civil service. This brought us back to important questions about class reproduction and the interconnections of Classics, élite education, and racism within the British empire (Vasunia 2013; Goff 2013).

All four cases above speak to the “non-performative” (Ahmed 2012) nature of a politics of recognition and how many contemporary liberal policies such as “multiculturalism” and “diversity” do not bring into effect what they claim to be doing. These discussions are inevitably unsettling for the students because they reveal important insights on our lives in a settler colonial state like Canada. By allowing students to discuss case-based historical-cultural media in small groups, we are able to facilitate conversations around the continuing presence of Orientalist tropes and make connections between colonial archives and contemporary politics—from the way countries like Iran and Palestine were portrayed by Trump and on social media, to Sinophobic responses to COVID-19, to how heritage tourism advertisements resort to self-Orientalizing tropes.

“Othered”: (Un)learning Orientalism through art projects

For their final assignment, students are asked to team up and co-create a piece of artwork that relates to the theme “Othered.” The piece in question can be of any type (visual art, spoken word, song, music, dance, etc.), as long as its format allows it to be presented or performed to the group on the last day of class. Students are encouraged to seek inspiration in the weekly readings and discussions, as well as in the other assignments for this course. They are also welcome to explore these themes in the light of their own experiences and relationship with the course’s topic. As a complement to the artwork piece, each team is asked to write an interpretive essay that both situates their creation within a broader historical context and articulates how it tackles issues and conversations that pertain to the contemporary relevance of (destabilizing) Orientalist tropes.

Our student art project “Othered” became a pedagogical tool we used to explore Orientalism through its continuing presence in our everyday lives and the role that it plays in generating personal contradictions and conflicting emotions in ways that social theory cannot completely capture. Visual art, poetry, and creative prose became ways to draw from the personal to locate the political and not the other way round. It has been a very personally moving experience listening to and viewing the products of our students’ work, some of which is exhibited in two online exhibits (Blouin and Daswani ed. 2020 and 2023).

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2012. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press

Alatas, Syed Hussein. 1997. The Myth of the Lazy Native: A Study of the Image of the Malays, Filipinos and Javanese from the 16th to the 20th Century and Its Function in the Ideology of Colonial Capitalism. London, Frank Cas & Co. Originally published in 1977.

Allen, Theodore W. 2012. The Invention of the White Race. New York: Verso.

Barkaskas, Patricia and Derek Gladwin. 2021. “Pedagogical Talking Circles: Decolonizing Education through Relational Indigenous Frameworks.” Journal of Teaching and Learning. 15(1): 20–38.

Blouin, Katherine. 2018. “Civilization: What’s up with that?” Everyday Orientalism. February 23.

———. 2023. “Canada is a metaphor: On the Doctrine of Discovery, Roman law and Genocide.” Medium. February 1.

Blouin, Katherine and Ben Akrigg 2024. The Routledge Handbook of Classics, Colonialism, and Postcolonial Theory. New York: Routledge.

Blouin, Katherine and Girish Daswani ed. 2020. “Teaching Orientalism through Art Practice: ‘Othered’, the Virtual Exhibit.” Everyday Orientalism. April 29.

——— 2023. “Orientalism through Time and Place: A Virtual Exhibit.” Everyday Orientalism. August 11.

Goff, Barbara. 2013. ‘Your Secret Language’: Classics in the British Colonies of West Africa. New York: Bloomsbury.

Madiou, Mohamed Salah Eddine. 2021. “The Death of Postcolonialism: The Founder’s Foreword.” Janus Unbound: Journal of Critical Studies, 1(1), 1–12.

Maracle, Lee. 2015. Memory Serves: Oratories. Edmonton, Canada: NeWest Press.

Mitchell, Timothy. 1988. Colonising Egypt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Quijano, Aníbal. 2000. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 533–580.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

Simpson, Audra. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Lives across the Borders of Settlers States. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Spice, Anne. 2016. “Interrupting Industrial and Academic Extraction on Native Land,” Hot Spots, Fieldsights, December 22.

Sabbagh-Khoury, Areej. 2023. Colonizing Palestine: The Zionist Left and the Making of the Palestinian Nakba. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New York: Bloomsbury.

Vasunia, Phiroze. 2013. The Classics and Colonial India. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yuzwa, Zachary. 2021. “The Fall of Troy in Old Huronia: The Letters of Paul Ragueneau on the Destruction of Wendake, 1649–1651,” In Brill’s Companion to Classics in the Early Americas, edited by Maya Feile Tomes, Adam J. Goldwyn, and Matthew Duquès, 398–423. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.