TikTok and the Pandemic: A State of Non-Exceptionality for Domestic Workers in the Gulf States

From the Series: Where Have All the Workers Gone? Re-Imagining Labor in the Post-Pandemic World

From the Series: Where Have All the Workers Gone? Re-Imagining Labor in the Post-Pandemic World

Migrant populations make up over 50 percent of the total population in the Gulf states. Migrants are managed by anti-integration policies, resulting in a significantly segmented social landscape. This region is also home to the highest number of migrant women hired as housemaids in the Middle East. This job category is exclusively comprised of women from Southeast Asia and Africa. Encompassing daily tasks such as cleaning, cooking, childcare, and elderly care, it is monitored by a sponsorship system (kafala) that is required to obtain a visa and a residence permit. Domestic workers are typically sponsored by the families they serve. The kafala prohibits them from resigning without the employers’ consent and criminalizes attempts to flee. Despite recent labor laws in most Gulf countries, domestic workers suffer from precarious conditions, such as inadequate or nonexistent living quarters, passport confiscation, overwork, and an overall lack of enforcement of their rights. Although the safety of overseas citizens has become a steadfast principle in some sending countries, diplomatic protection can also be insufficient to ensure the protection of these women once in the Gulf.

In contrast to other migrant-dominated sectors visible in public spaces (such as taxi driving, waiting tables, cashiering, or construction work), domestic work remains largely hidden. Domestic workers live in the homes they serve with limited opportunities to go out (typically only on Fridays, their designated day off), and their contracts stipulate that they must not disclose details about their employers’ privacy. The importance of privacy in the Gulf is reflected in many other aspects, starting with the architectural layout of houses, which includes guest rooms. Guests are welcomed in these areas but have no access to the rest of the house, especially not to the service quarters where domestic workers carry out their duties. Based on social and symbolic representations, this spatial division reinforces the invisibility of domestic labor. In Kuwait, some women I interviewed reported being housed in pantries, arguably among the least comfortable spaces in the home. While leaving the house without employer permission is forbidden by law, others were denied their weekly day off for one day given every one or two months (Breteau 2025).

What would happen, then, if kitchens, bathrooms, and domestic workers were suddenly propelled onto social media? This question has been a growing concern in the Gulf since the emergence of TikTok, one of the most-used applications worldwide. Noticeable by their work attire and specific hashtags, domestic workers use TikTok to highlight their poor living conditions. They express their concerns, seek assistance, and foster an online community, making online visibility an empowering tool to reclaim their image and rights (Chee 2023). However, the platform’s parameters induce random content generation, which raises questions about the temporal accuracy of the realities portrayed.

TikTok’s global popularity surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, evolving from a Chinese karaoke app into a widely used video-sharing platform (Mohamad 2020). In the Gulf, pandemic management included various measures that required many migrants to return to their home countries to curb the spread of the virus. However, school and workplace closures simultaneously increased the demand for domestic labor. Preexisting abuses intensified during lockdowns, exposing the heightened vulnerability of domestic workers. While most domestic workers were retained, and return was facilitated for those who had left, their already precarious situation worsened due to increased employer control and enforced isolation.

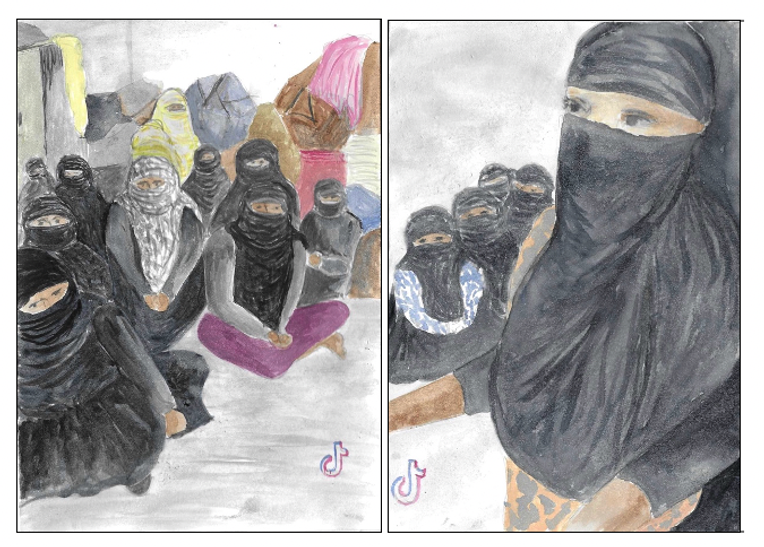

Although the COVID-19 crisis waned in late 2021, I still encountered videos from its peak. One video made me reflect on temporal overlaps between analog and digital, since the original creation date was not provided. Bags and packages piled up in the background of a cramped room; about forty women, heads and faces covered, were seated on the floor. The camera focused on one of them. Holding her hands to the sky, she shouted in French over the hubbub: “Four months, we can’t come back home, we beg you, help us . . . It’s Africa that is being humiliated; it’s the humiliation you see here!” The woman’s voice rose angrily: “Look at us! Help us, pity us! We are in Kuwait, for so many years we’ve been here, we’re being held back, they don’t want us to . . .” The video abruptly ended mid-sentence, leaving me perplexed. Have these women been confined for four months, or for “so many years”?

Since the video did not include its original publication date, users in the comment section expressed confusion about whether it dated from the pandemic or more recently. The unknown publication date of this video, its potential republication, the date of the comments, and my access to them raise questions about the cumulative effect of divergent analogical and digital timeframes. Although this is not specific to TikTok, the juxtaposition of analog and digital timeframes furthers understanding of the Internet as analogically anchored. As a result, the repercussions of the pandemic and their online manifestation beyond its official termination highlight the “non-exceptionality” of the circumstances in which domestic workers found themselves during this period (Mani 2022: 10).

The Internet acts as an empowering tool for expression, but it also poses a potential risk to domestic workers, as illustrated by imprisonment cases in the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait for TikTok videos deemed a breach of privacy and a disrespect for the country’s image. The combination of TikTok’s and the pandemic’s timeframes highlights the non-exceptionality of the challenges faced by domestic workers beyond the temporariness of their employment and controlled invisibility. For users from marginalized communities, digital platforms serve as outlets that reveal significant dynamics of exclusion. By circulating their voices beyond a given moment, they also resist their erasure; they demonstrate how social (in)visibility is not only a matter of space and norms, but also of temporality.

Breteau, Marion. 2025. “TikTok Affordances Among Foreign Domestic Workers in Kuwait: Between Connective Leisure, Ethical Empowerment, and Migrant Regulation.” CyberOrient 19: 4–28.

Chee, Liberty. 2023. “Play and Counter-Conduct: Migrant Domestic Workers on TikTok.” Global Society 37, no. 4: 593–617.

Mani, Lata. 2022. Myriad Intimacies. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Mohamad, Siti M. 2020. “Creative Production of ‘COVID-19 Social Distancing’ Narratives on Social Media.” Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 111, no. 3: 347–359.