“I learned that you had spent a lifetime equally devoted to the conviction that words are not good enough. Not only not good enough, but corrosive to all that is good, all that is real, all that is flow” (Nelson 2016, 6).

I learned, or always knew, that words capture. They tend to arrest the real into categories, when what is real is to be found in excess. Standing in front of the group of thirty-five young bright minds, teaching my first independent course, words often alluded me. The immense responsibility of making something land and stick, and on a topic such as gender and sexuality, confronted me with the fact that some things are to be explained, while others are to be experienced outside of language, or alongside it. The boundary between these two is personal. At least for me it was formulated in feelings; in gauging the atmosphere in the classroom, how my students responded to certain topics, my anticipation of “difficult conversations” that would require of all of us to loosen our grip around language, and “express without formulating” (Blanchot 1993, 36). My own verbal paralysis led me to decide that an equally important move in creating a classroom where excess can thrive is to offer my students a chance to engage with the classroom material in ways that are not strictly verbal.

Inspired by the communal aspects of DIY fringe culture of zines and the activist aspects of scrapbooking, I built these into my syllabus as teaching tools and legitimate forms of knowledge production. Zines have been around me since the time I developed a knack for “minor literature.” These non-commercial, cheap-to-make, DIY-by-nature publications sport the voices of people on the “fringes” of either society or the publication world. Through my foray into the history of zines I stumbled across Vise Versa, one of the first LGBT magazines, printed by Edythe Eyde (pen name “Lisa Ben,” an anagram for lesbian) in the 1940s. She shared her writing with her friends, who would then pass it on to their friends. Even though she only printed a few (maximum of ten) zines they found their way to people who needed them. And I certainly was one of them. My favorite time period of zine making is the 1990s and 2000s. Riot Grrrl, a collective that actively encouraged women to participate in the public discourse, produced numerous zines ranging from manifestos, collaborative minizines, anonymous pieces advocating for feminist vigilantism gang-style, anarchist feminist writing, and many more. The collective, inspired by Queercore zines and bands, cleared up a space for younger queer kids of diverse genders. Queercore, or homocore, a part of the anarcho-punk subculture, took up as its mission a broad critique of homophobia inside the subculture and society at large. Some of these zines are preserved by QZAP (Queer Zine Anarchist Project), first launched in the early 2000s. POCZP (POC Zine Project) was launched in 2015 to archive the works of POC and make them shareable, searchable, and distributable.

Scrapbooking, on the other hand, has its roots in the Middle Ages and originated from the literate elites of the society. In the late eighteenth century people started using “extra-illustrating”—a technique for customizing books by adding additional illustrations to them. This practice was popularized by James Granger, whose name became the synonym of the practice of customizing books. Grangerizing was more than a means to creatively engage with print; the practice was used for political and social change. In 1839 a co-authored book titled “American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses” was published. It was a collection of scraps from newspapers that accounted for the horrific treatment of slaves by their owners. The practice of scrapbooking allows for different things: substantiating the written evidence by the visual means (as was the case with the aforementioned book), or juxtaposing the visual and written for a third, excessive (extra-illustrated) object to emerge. In my classroom, I drew on the traditions of both zine making and scrapbooking to allow for my students to experience the process of creating realities outside of language per se, or to add the visual to the verbal to drive their points across.

My syllabus was organized in five modules, each tackling a hegemonic aspect of the sex/gender system. We discussed biomedical construction of gender and patriarchy, capitalism, race, and film and media. The fifth module was organized around doing sex/gender and sexuality differently. I wanted them to be able to understand how the systems around them influence them, but I also wanted to agitate for lines of flight. I prompted my students to imagine a pathway for disrupting this hegemony, and look for potential to enable new forms of life, thought, and relations. I am unsure how many opportunities I will get to teach again, and I wanted to use my time to create a community, if only a short-lived one. What better way to teach “Gender and Sexuality” than to use practices of cultural production that were at the disposal for people who have been discriminated against by the system of racist-hetero-patriarchal hegemony?

I had three explicit reasons for my choice. I wanted to decenter academic publishing as the only legitimate realm of knowledge production. First, academia, as any other institutional setting, is mired in restraints that often insist on staying close to a particular form of language. Having a significant number of first-generation college students in the classroom, I felt an imperative to allow for a diversity of forms of expression. I wanted to show my students what I believe: Knowledge comes from various sources, and institutions don’t have a sole claim on it. Second, the topics we were covering in the class are difficult by default, and yet they are exponentially more difficult for certain groups of people. I wanted my students to tap into the historical lineage of expressing differently, for a cause, or just for the thrill of it. And, more importantly, outside of the boundaries of institutional language. I was not only interested in doing so because of the final product, but the process itself. Playing with visual and textual elements allows for a different form of engagement with ideas. I find the process cathartic. I thought some of my students might feel the same way. And lastly, and very obviously, using means of teaching and evaluation that are strictly shaped by written pedagogical traditions exclude a vast number of people who are uncomfortable with the said tradition.

Out of thirty-five students I had in the classroom, fifteen had submitted their finals in the form of zines or scrapbooks. I insisted that I was not grading the mastery of their work (as I don’t do with academic essays either). I, myself, don’t know how to draw a stick figure, and yet I doodle all the time. I wanted my students to have a chance to doodle for knowledge as well. What I asked them to do instead is to show an intellectually honest engagement with class material. And all of them did wonderfully.

Here I want to present two zines and one scrapbook that I had the privilege to read and grade. I find these pieces inspiring and I turn to them often just to marvel at the chance of being able to work with these brilliant people. I also hope that people who find themselves in the role of teachers and mentors might consider possibilities to teach alongside language. The effects of this practice are intellectually invigorating, soul nourishing, and pedagogically and politically powerful.

Zines

“How Does the Patriarchy & the Sexist Ideals It Purveys Negatively Frame the Concept of Femininity” by Emily Hinckley

In this zine Emily analyzes the pathways of the social construction of femininity, which ends up associated with weakness. She analyses patriarchy as a system of classification, the social construction of gender conflated with sex and embodied in biology talk and how this seeps into labor (paid and unpaid, material and invisible). She ends with the conclusion that is one of the lines of flight. This zine comprehensively merges a part of the academic literature on the subject and the personal understandings of what it means to inhabit a patriarchal system.

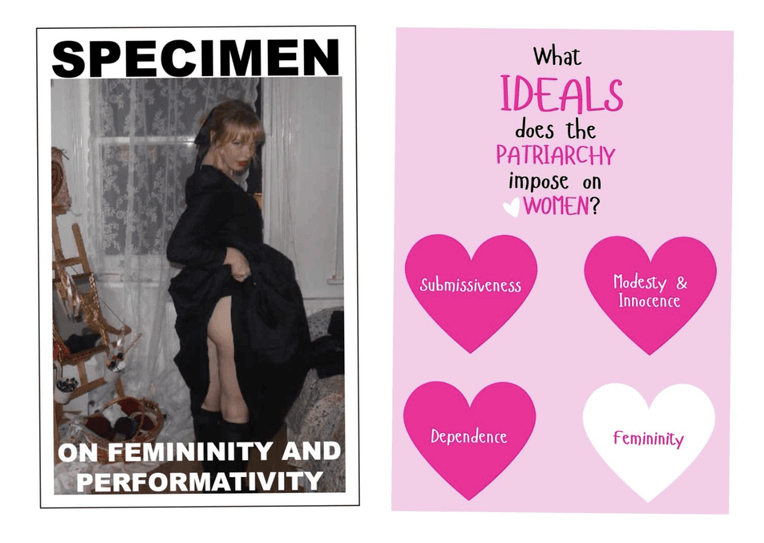

“Specimen. On Femininity and Performativity” by Gwyneth Bessey

In this zine Gwyneth writes from the intersection of capitalism and patriarchy and leads us through the typology of personality types available to women as she observes them. The zine is designed as an inside of a magazine, emulating its content through its form. Using materials we covered in class, Gwyneth also makes us question the sources of the narrow possibilities for being “feminine” and poses questions in lieu of ways out.

Scrapbook

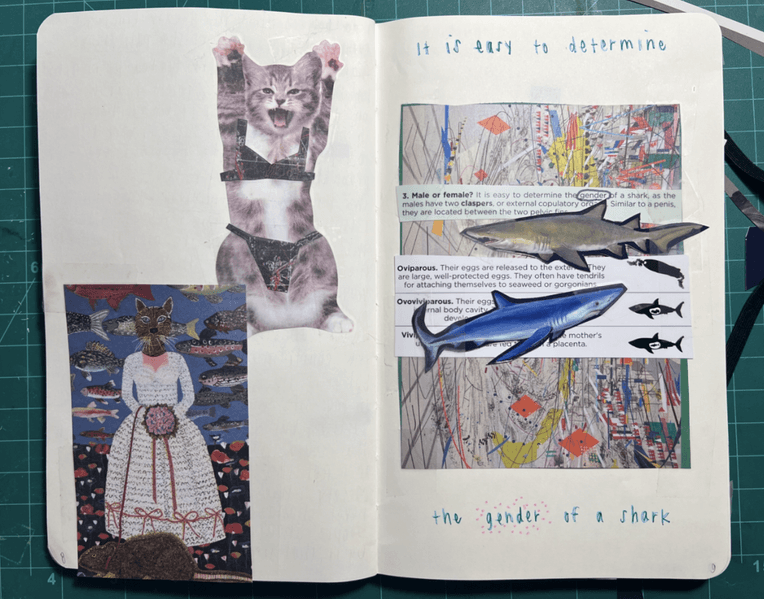

“A Diary of Concepts Covered in Class” by Audrey Smith

In this analogue scrapbook, Audrey creatively merges the knowledge of concepts covered in class, her own reflections on the topics she is interested in, and interludes of collages as respites from the verbal. Audrey covers the biological underpinnings of the sex divide (conflated with the gender “divide”) and follows with its entrance into patriarchy, workforce, and race. Reflective and self-aware, Audrey warns us about potential biases related to her positionality.

Holding On

By incorporating zines and scrapbooks I witnessed how students used them to hold tension—between theory and feeling, the personal and the structural, language and its limits. The documents became not just sites of articulation, but of refusal, play, and most importantly, (self-)care. They held onto difficulty and in doing so invited a different kind of learning—one that lingered and mattered beyond the grade. I was moved by the intimacy of their work, and reminded again that learning, too, is a form of relation. The question that is still unresolved for me is what might emerge if zine making was not positioned only as a final output, but as a practice threaded through the semester? If I were to do this again, I would give more class time to the making itself—to the process of thinking materially, cutting, assembling, pausing, and wondering.

References

Blanchot, Maurice. 1993. The Infinite Conversation. Translated by Susan Hanson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Nelson, Maggie. 2016. The Argonauts. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press.