I never thought of drawing in the field. But my PhD supervisor surely envisioned it for me: in our last meeting before leaving for the upcoming “year in the field” rite of passage, she handed me a daring shocking pink A5 hardcover notebook. “You mentioned drawing in your A-Exam on writing experimental ethnography,” she gestured, overlooking the thick blank pages as an inviting provocation. I left the office with the lightness and excitement of newly acquired wings, but also with just a pinch of impostor syndrome: I sure did think, read, and write about sketching in the field and how others went about it, but it never crossed my mind that I, myself, could actually do it. I just don’t know how to draw. And so I would never upset the fragile fieldnote ecosystem with doodles. Until years passed and I realized I needed to reconnect to “the field” with a joy that might otherwise fade out.

Fieldwork Context

I conduct “fieldwork” somewhere within my living sphere: Cambodia is both where I go home to and do research with Cham Muslim communities. The Cham family that took me in, long before I thought of becoming an anthropologist, and I have developed a deeply personal relationship. Yet, while this attachment and the permanence of this relationship strengthen my familiarity and stability within the community much beyond fieldwork, my passion for anthropology has been taking a hit: call it academic depression, work burnout, or just disciplinary fallout. Over time, I just couldn’t face another day doing research. Things had gotten hard and then harder, and then just all too hard. Forget about having to face contract renewals and job market aspirations: I didn’t even want to do “fieldwork” anymore, just as I was getting back to the very community I had become part of. Getting professionally sloppy is one thing, but when your sloppiness threatens to affect the communities you are personally committed to, the layers of guilt for not showing up become intricate. I had to think of an intervention, or at least of other ways to do things. An alternative practice that wouldn’t focus on the end result but rather be embedded in the mere accountability of being present: one that wouldn’t overwhelm me with the burden of the heavy-duty of “daily fieldnotes” but rather open up to the lightness of being in co-presence. Now wasn’t the time to think about the ominous “second tenure track project” in a land of no-tenure, or about “how to do things right” when everything around had gotten so wrong. It was time to go back to feeling good, being good, and doing good.

Enter sketchnotes.

Field-Sketchnotes

Since all grandiose plans were falling apart (jobs, grants, publishers, overall professional self-worth…), I felt the need to switch to all things small and process oriented (as opposed to outcome oriented, through hiring/renewing committees). As academics, I think we are in dire need of tiny paths of progression that take into account our fragmented lives, bandwidth, and skills. I found solace in feminist approaches to ethnographic works that were doing just so (Günel et al. 2020, Bedi et al. 2021). But if, as a multimodal anthropologist, I had reached such a point of dissociation that I couldn’t stomach my usual combo of photo-video-sound work and writing, how could I get into something as tempting but also as new and as intensive as drawing? It just felt way too self-indulgent: who has time to draw when the inbox still screams, dishes pile up in the sink, and news of next-door wars are screened on repeat?

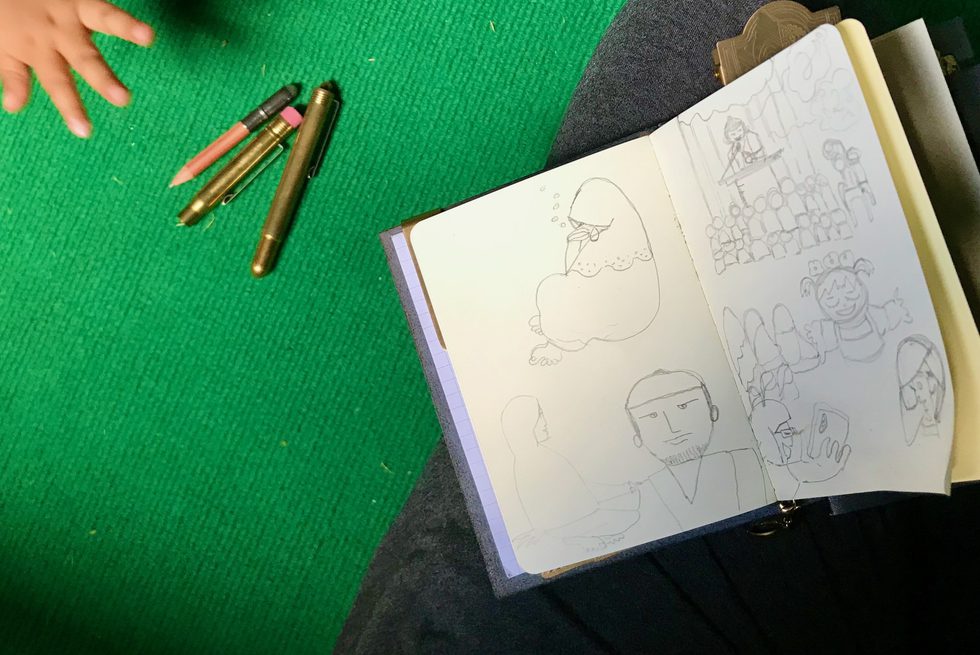

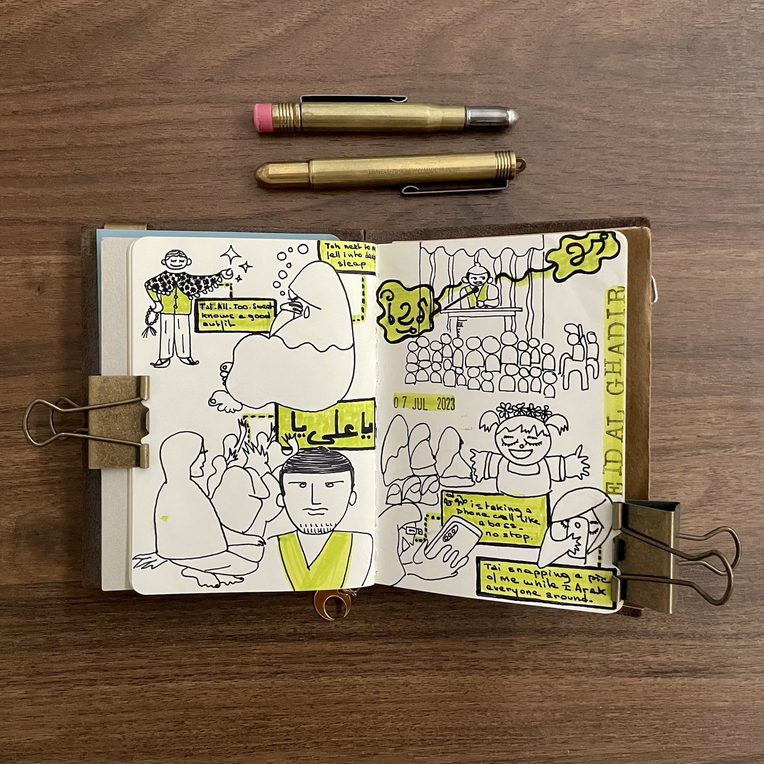

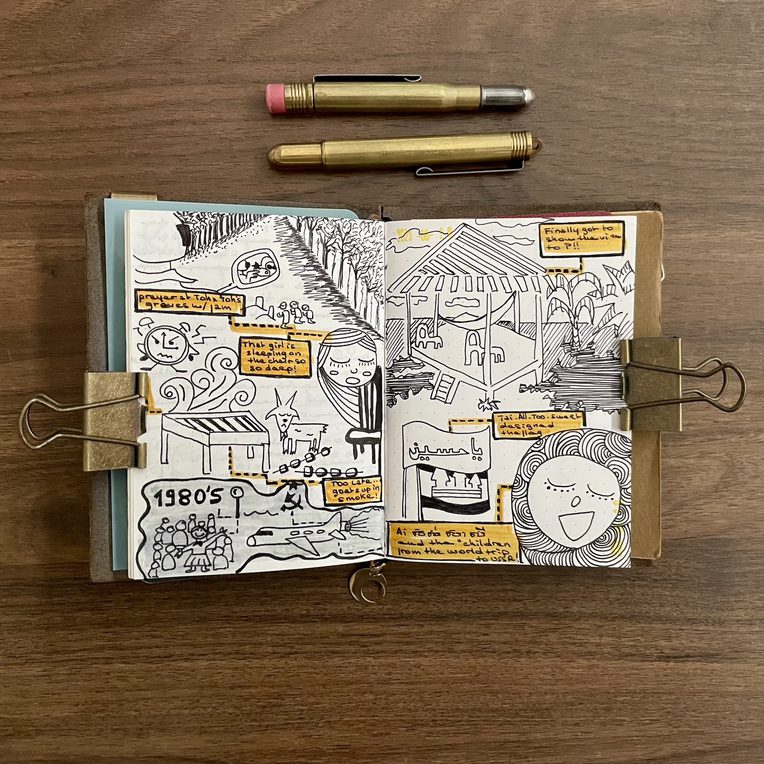

In moments of escape and procrastination, I took a deep dive into sketchnotes: the practitioners were masters of clarity, moods, and ideas, but never seemed to be out-of-reach award-winning artists (Lamm 2017, Mills 2019, Neil 2024, Rohde 2012, 2014). They excelled at thinking and putting their thoughts down on paper with playful easy doodles, a great sense of page structure, and a balancing act between visuals, negative space, and quick bursts of texts and titles. Sketchnotes turned information into something light, doable, digestible, and memorable. Quite a metaphor for everything I wanted my ethnographic fieldnotes to be, and yet were everything but. The A5 notebooks that I had so long loved to align on shelves as proud rainbow badges demanded to be fed with “thick descriptions” that I didn’t have in me anymore. I decided to equip myself with a passport-size traveler’s notebook and to try my luck on small field-sketchnotes. Just as I used a pocket size jotter for writing in the moment along with a larger notebook for journaling after the fact in my ethnographic note-taking, my sketchnotes were to come in two phases: they either started on the spot, as drawings (pencil-sketched in the moment and revised/improved in the evening or within a couple of days) or they were put together after the fact (and therefore based on written scribbles or memories).

A DIY Approach

Of course, I didn’t really know where to start: I hadn’t drawn since I was a kid, and I wasn’t aware of any course or manual on “how to go about the most perfect ethnographic sketchnotes in the universe.”[1] However, I was ready to embrace the DIY improv approach since my goal was to try things out rather than aim for a specific result. I didn’t really have any criteria to compose the notes. If anything, I was interested in the process itself. Here are a few similarities and differences that I noticed—as a newbie—between the drawing and the writing of fieldnotes.

Doing it: It’s an old (yet still very valid) anthropologist trope to complain about our lack of training in ethnographic writing (whether we think about the write-up toward publication or the fieldnotes themselves). Additionally, multimodal anthropologists are particularly seasoned in this isolation: we not only have to find ways to train our own selves through audiovisual ethnographies, but also to educate students as well as colleagues in the value of those. While graphic ethnography readings were essential to equip me with a sense of openness and validation, documenting myself about sketchnotes enabled me to understand how to actually do it and start practicing. Ultimately, I decided to just aim for intuitive simplicity: my goal was a travel journal of sorts rather than an ethnographic report. The latter just sounded too intimidating: it would have to be serious, exhaustive, and very realistic, all things that I didn’t feel capable of doing with my overall exhaustion and drawing skills at level zero. Speaking of level zero, I found assistance in copying illustrators that I already personally liked in order to learn, because they excel at conveying moods, vibes, and lives in a way that the learning “artist” can easily reproduce: all I wanted was an accessible upgrade from stick figures, not a museum collection of engravings. Keeping it simple allowed me to actually enjoy the process, which again was central to the whole experiment.

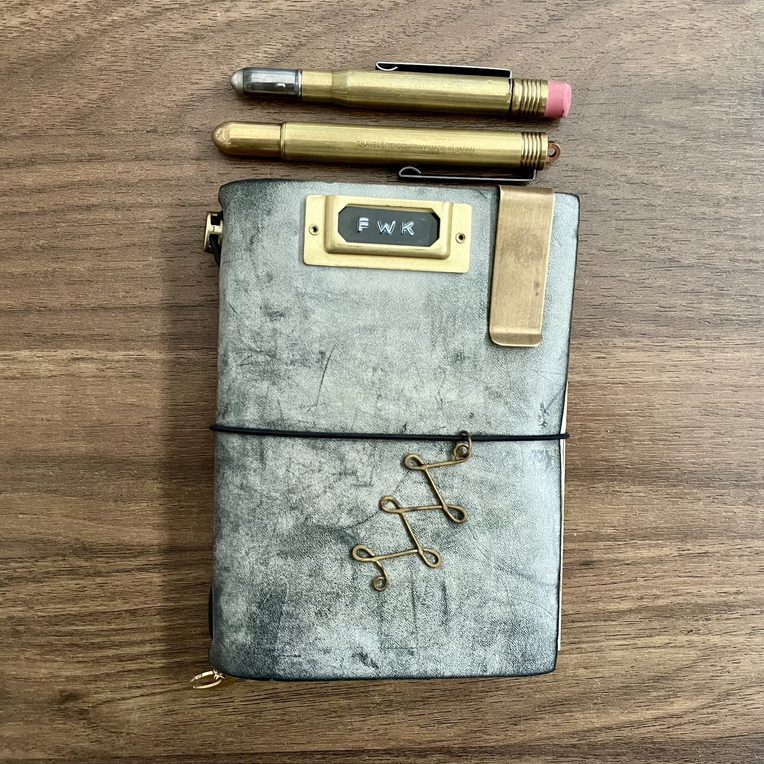

Setup: I used a traveler’s notebook setup mainly because as a stationary fan, I needed an excuse to get yet another one. Also, the system binds together small notebooks or inserts together, which allows for both order and flexibility. My fieldwork dedicated setup combines three inserts: one for quick written notes, one for quick “in the moment” sketches, one for sketches done later on, and a small pouch to collect random add-ons (name cards, receipts…). They are all dot grid because it is discreet enough not to be too overbearing but still provides a bit of guidance. I love using this little notebook. I never was a laptop-in-the-field kind of person because screens, to me, often equal “labor” too much. Plus they are way too costly to be risked. Still, the A5 thick notebooks had just become a little too overbearing. The smallness and flexibility found in that new setup were an essential material contribution to a process I was to look forward to, rather than procrastinate on.

Audience: Sketchnotes in the fields of education at large, design, and marketing are generally aimed at a broad public. They are actually used to convey a message that aims to be more inclusive than dense writing would. My goal, however, was not to compose ethnographic fieldnotes for others, but primarily for myself. This might limit the legibility to the outsider: the mix of languages can seem all over the place (I think in English, French, and Khmer; my interlocutors think mainly—although not exclusively—in Khmer and Cham, and sometimes we exchange thoughts and words of Farsi and Arabic), so this apparent mess is actually on par with my written notes. On the other hand, the visual aspect of the notes made them hyper-legible in the drawing moment and generated more conversations and companionship than written notes ever did. Scribbling down notes in the moment was never done, in my experience, without interactions, even when those were only relying on words: readers of Cham would comment on the “cuteness” or “clumsiness” of my writing; those who couldn’t read my (English and French) handwriting would often ask what I was writing about. But drawing of course generates its own load of giggles, surprises, and pauses. Despite the well-established fact that “ways of seeing” (Berger 1990) (and therefore representing) are never true universals, the doodles were ‘legible’ enough for onlookers to figure out what and who they were about. Kids, of course, showed up the most, and their comments were the most direct: “That’s a big face!”; “If you don’t have colors, what’s the point?”. I am now learning different shape-making approaches and styles to take in such comments, which I am still very much processing.

Learning from the Experience: What Was Gained/Lost

While I enjoyed using sketchnotes as my go-to fieldnotes, they obviously didn’t magically turn into an overall academic everything-better-forever-and-after magic cure. Still, they did bring joy back into the short bursts of visits to the community, allowing a combination of the personal with the ethnographic, while finding joy again in being an anthropologist at work.

I will definitely keep prioritizing sketchnotes in the field over other forms of notetaking that, over time, had become, to me, such a drag. But sketchnotes also come with the same limitations that different forms of “field” note-making can bear: sometimes I just dream of not recording anything at all, being in the moment and leaving it at that. Sometimes I let go and forget everything I was supposed to remember: it’s too late and there is no getting the memories back, the guilt settles in. No matter how fun doodling can be, when associated with ethnographic goals it does become work and, I don't know about you, reader, but no matter how much I love my work, sometimes I just don’t want to work at all. I have also noticed some limitations in terms of the sketchnotes themselves that I will now share in case you want to try your hand at them.

Chasing realism: As you can see in the samples pictured in this article, I opted for non-realistic doodles. This is not only because of my own drawing limitations and personal aesthetics, but also as a representational intervention of refusal. With this kind of unrealistic drawing it is impossible for me, or anyone for that matter, to take the field sketchnotes for granted as objective witnesses of reality. I think the debate over subjectivity in anthropology has long been settled, so there is nothing really new here, but since the sketchnote centers and emboldens those claims right from the first look on the page, there cannot be any confusion: it resolutely embraces the subjectivity of the ethnographer, the partial vision, and, in sensitive contexts, the impossibility to identify interlocutors and necessity to anonymize them. It brings a bold and in-your-face support to the argument that anthropology is by definition biased, situated, partial, deeply affective, and relational, and that ethnographic descriptions can only be re-used, reproduced, and cited with limitations. While this may not work for everyone, it does for me and other graphic anthropologists who have long made this case (Ingold 2011, Taussig 2011, Kuschnir 2016, Causey 2016, Bonanno 2023, Sacks 2020, Theodossopoulos 2024).

Chasing thickness: Following up on the previous point, my sketchnotes also resolutely move away from “thick description.” If thick description is what one is after, one could claim that it might be attainable in graphic representation: the drawing skills and orientations of early travelers and ethnographers, indeed, aimed to visually convey densely saturated scenes. But again, my own limitations and aesthetics work counter this goal. Most of the time I was fine with that, as I have learned to embrace more minimalist and down to earth approaches to fieldwork, which actually translate in heightened co-presence and relationality. But once in a while, I felt a pinch of regret and guilt: I had been trained early on to do things the “thick” way, and have tended to compare my present and future ethnographic work to that of the past, something neither realistic nor enviable. Multimodal anthropology has, in fact, demonstrated that much more than thickness can be gained in resisting transparency, completion, and collection, and instead embracing ambiguity and the sensory as political gestures disrupting representational status quos of power (Takaragawa et al. 2019, Alvarez Astacio et al. 2021, Guzman and Hong 2022). More specifically, graphic anthropologists have shown that drawing can legitimately be used in dissertations (Sousanis 2015, El Helou forthcoming), theoretical work (Alfonso and Ramos 2004, Causey 2016, Jain 2019), monographs (Povinelli 2021, the ethnoGRAPHIC series 2017-2021), collaborative processes (Haapio-Kirk and Ito 2022), and reciprocal opacity in tense contexts where documentation threatens of surveillance and censorship (Lawlor 2015, Bonanno 2023).

Chasing universality: Finally, what I have learned and I am still learning with sketchnotes is to dig deeper into the topic of visual representations, and how those are always culturally and historically situated in relation to power. This is obvious to us anthropologists, but seemingly “mundane” doodles take that to another level. We are used, trained, and professionalized into words primarily if not solely, and words do equip us with a rich vocabulary for things we want to describe, whether they materialize in the real world or not. We might not question all the metaphors or abstract concepts we use when writing up ethnographies, or in the ways we and those around us see and think the world. Drawing calls us upon that: how we represent to ourselves and to the rest of the world is grounded in either very concrete ideas (it’s hard to draw “affect”), or in deeply poetic imaginaries (it’s all about “affect”). This is something that came to the forefront of my turning to sketchnotes in the classroom, a topic I elaborate on in the next piece of this series.

Footnotes

[1] It is only later on (of course) that I found what could have been the perfect resources in Kuschnir (2016) and Bonanno (2023), which, while not focused on sketchnotes, are ideal to dive into the practice of sketching in the field. The instagram page @illustrating_anthropology is also a fantastic resource.

References

Alfonso, Ana Isabel, and Manuel João Ramos. 2004. “New Graphics for Old Stories Representation of Local Memories through Drawings.” In Working Images: Visual Research and Representation in Ethnography, edited by Ana Isabel Alfonso, László Kürti, and Sarah Pink, 72–89. London: Routledge.

Alvarez Astacio, Patricia, Ethiraj Gabriel Dattatreyan, and Arjun Shankar. 2021. “Multimodal Ambivalence: A Manifesto for Producing in S@!#t Times.” American Anthropologist 123, no. 2: 420–27.

Bedi, Tarini, Aditi Aggarwal, Josephine Chaet, and Lakshita Malik. 2021. “Feminist Pedagogy through the Small Fieldnote.” Feminist Anthropology 2, no. 2: 199–223.

Berger, John. 1990. Ways of Seeing: Based on the BBC Television Series. Reprint edition. London: Penguin Books. Originally published in 1972.

Bonanno, Letizia. 2023. “How to Draw Fieldnotes.” In An Ethnographic Inventory: Field Devices for Anthropological Inquiry, edited by Tomás Sánchez Criado and Adolfo Estalella, 52–61. London: Routledge.

Causey, Andrew. 2016. Drawn to See: Drawing as an Ethnographic Method. Illustrated edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

El Helou, Maya. Forthcoming. “Queer & Trans Antagonism Against the Consortium of Let Die in Beirut.” PhD diss., University of Toronto.

Günel, Gökçe, Saiba Varma, and Chika Watanabe. 2020. “A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography.” Member Voices, Fieldsights, June 9.

Guzman, Elena H., and Emily Hong. 2022. “Feminist Sensory Ethnography: Embodied Filmmaking as a Politic of Necessity.” Visual Anthropology Review 38, no. 2: 184–210.

Haapio-Kirk, Laura, and Megumi Ito. 2022. “Turning Points.” Special Theme: Ethno-Graphic Collaborations: Crossing Borders with Multimodal Illustration. Trajectoria: Anthropology, Museums and Art 3: 1–8.

Ingold, Tim. 2011. Redrawing Anthropology. Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate.

Kuschnir, Karina. 2016. “Ethnographic Drawing: Eleven Benefits of Using a Sketchbook for Fieldwork.” Visual Ethnography 5, no. 1, 103–134.

Lamm, Eva-Lotta. 2017. Secrets from the Road. https://secretsfromtheroad.wordpress.com/.

Lawlor, Veronica. 2015. The Urban Sketching Handbook Reportage and Documentary Drawing: Tips and Techniques for Drawing on Location. Beverly, Mass: Quarry Books.

Mills, Emily. 2019. Art of Visual Notetaking: An Interactive Guide to Visual Communication and Sketchnoting. Illustrated edition. Beverly, Mass.: Walter Foster Publishing.

Neill, Doug. 2024. “The Verbal to Visual Notebook.” https://verbaltovisual.com/the-verbal-to-visual-notebook/.

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2021. The Inheritance. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rohde, Mike. 2012. The Sketchnote Handbook: The Illustrated Guide to Visual Note Taking. Berkeley, Calif.: Peachpit Press.

———. 2014. The Sketchnote Workbook: Advanced Techniques for Taking Visual Notes You Can Use Anywhere. Berkeley, Calif.: Peachpit Press.

Sacks, K. 2020. “Drawn in the Field.” entanglements 3, no. 1: 7–30.

Sousanis, Nick. 2015. Unflattening. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Takaragawa, Stephanie, Trudi Lynn Smith, Kate Hennessy, Patricia Alvarez Astacio, Jenny Chio, Coleman Nye, and Shalini Shankar. 2019. “Bad Habitus: Anthropology in the Age of the Multimodal.” American Anthropologist 121, no. 2: 517–24.

Taussig, Michael. 2011. I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Theodossopoulos, Dimitrios. 2024. “Graphic Ethnography.” In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Hillary Callan and Simon Coleman, 1–14. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.

ethnoGRAPHIC Series:

Carrier-Moisan, Marie-Eve, William Flynn, and Debora Santos. 2020. Gringo Love: Stories of Sex Tourism in Brazil. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Hamdy, Sherine, and Coleman Nye. 2017. Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Jain, Lochlann. 2019. Things That Art: A Graphic Menagerie of Enchanting Curiosity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sopranzetti, Claudio, Sara Fabbri, and Chiara Natalucci. 2021. The King of Bangkok. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Waterston, Alisse and Charlotte Corden. 2020. Light in Dark Times: The Human Search for Meaning. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.