In the previous post of this dual series on turning to sketchnoting as an anthropologist, I focused on incorporating visual thinking and drawing in ethnographic fieldnotes. I elaborated how the current context of overwork in universities, and the overall climate of academic depreciation led me to look for small, fun, and joyful interventions in the everyday in general, and in anthropological work in particular. This now includes turning to sketchnotes in teaching and integrating them into the classroom.

Why Integrate Sketchnotes in Teaching?

As explained previously, I began to gravitate toward sketchnotes as a positive, light, and fun tool to foster visual thinking and convey clear, simple, and playful messages through a combination of basic drawings and short bits of writing. As I started to wonder how to bring sketchnoting to the classroom, I was already familiar with discussing drawing in ethnographic courses: as a grad student teaching an ethnographic writing first-year course, I had included a section on drawing in the field. This was a moment in the syllabus that I felt compelled to test again in an anthropology graduate seminar on memory and history, as well as in two methods-focused undergraduate courses between 2021 and 2022. But at this point, while students in different places at different levels and I had had generative conversations on drawing and anthropology, I had yet to take a pencil myself. And while I always left the door open for sketching in students’ creative endeavors, I had never envisioned the activity as a course requirement. By the time I actually embedded sketchnotes in my syllabi in Fall 2023 - Spring 2024, I had gained some experience discussing sketchnoting but still felt like an imposter actually teaching it.1] I kept reminding myself that, if anything, I was hopefully a much better teacher of documentary filmmaking than an actual filmmaker, so why not try?

The desire to bring back the fun into the classroom and experiment with the new in my pedagogical approaches, along with the deeply seated conviction that some of the students would find some use (and pleasure) in continuing with sketchnotes in the future, were the main drives. But the timing also coincided with the rise of AI and ChatGPT use on campuses. I knew that with time I would be able to immerse myself in the new technology and find ways to embed it in productive and stimulating activities, but for now I just wanted to take a step back and slow down to really consider: how do we think our thoughts when left to our own devices? I wanted students to come along in the experiment, to move away from the lining-up of words that we are taught to master, but instead to think about how ideas come to us, how we picture them and give them shape on the page. Unless you are really comfortable with drawing (which for this article I am assuming most of us are not), the practice upsets our quick go-to responses: we can’t use the words, metaphors, references, and jargon that we take for granted to be of common understanding. We have to pry deeper, especially since most of us, if not artists in the making, don’t have the skills and resources to represent visually, or a common visual repertoire to fall back on. Ultimately I wanted sketchnotes to open a “thinking zone” in the classroom away from screen distraction. I also wanted to demonstrate the benefits of venturing toward the unknown and focusing on the experimental along with the stimulation of taking risks. If we could try something we were all “bad at” to start with, we could only get better at it. Those were the (one too many) ideas I was starting with. Now I had to actually think how they might (or might not) best serve a course.

Bringing Sketchnotes into Coursework

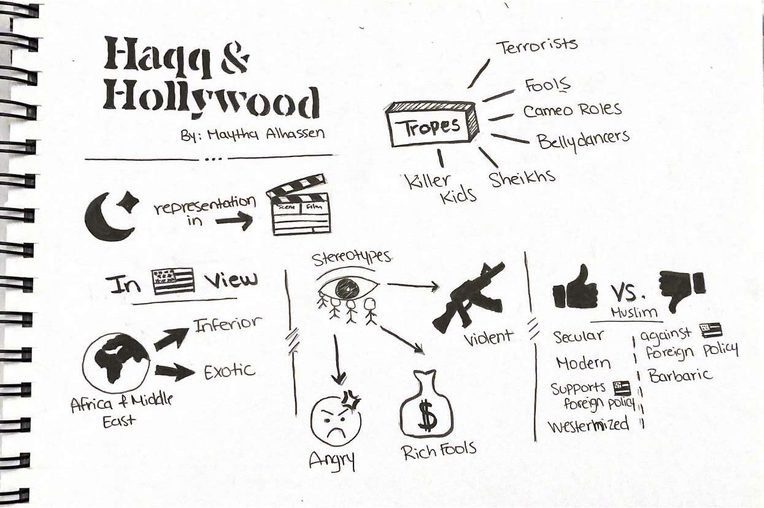

The process of sketchnoting was particularly fit for some of the courses I was teaching in the undergrad core curriculum in 2023-2024 at The American University in Cairo, and aptly constituted a playing field to question taken-for-granted universals and issues of representations: “Arab Society” (through the representation of Arabs and Muslims in Hollywood cinema) and “Kinship, Family, and Friends in Egypt.” The classroom would occasionally include a few minors in anthropology/sociology and a couple of students in graphic design, but most students were here to (often reluctantly) check off liberal arts requirements. I was therefore expecting a wide range of motivations and understandings. In this context, I approached sketchnotes as a tool for practice and thinking embedded in routine and repetition, so to create a comfortable space for students to begin to draw (the assumption being: everyone in the class is terrible at drawing, yours truly included).

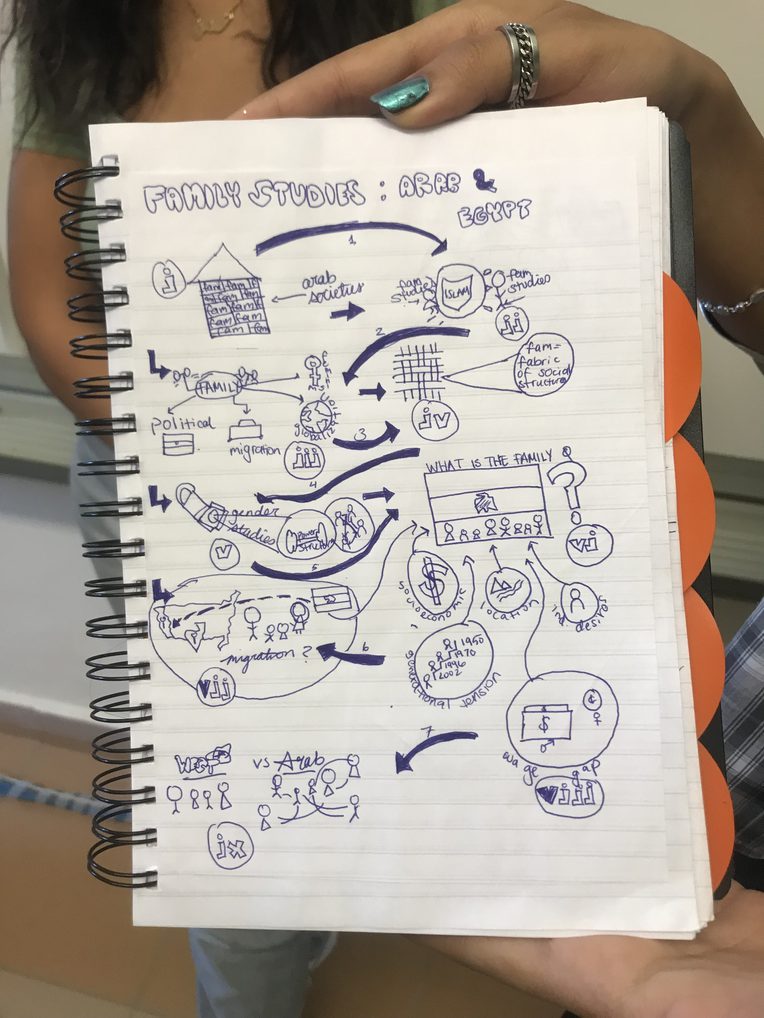

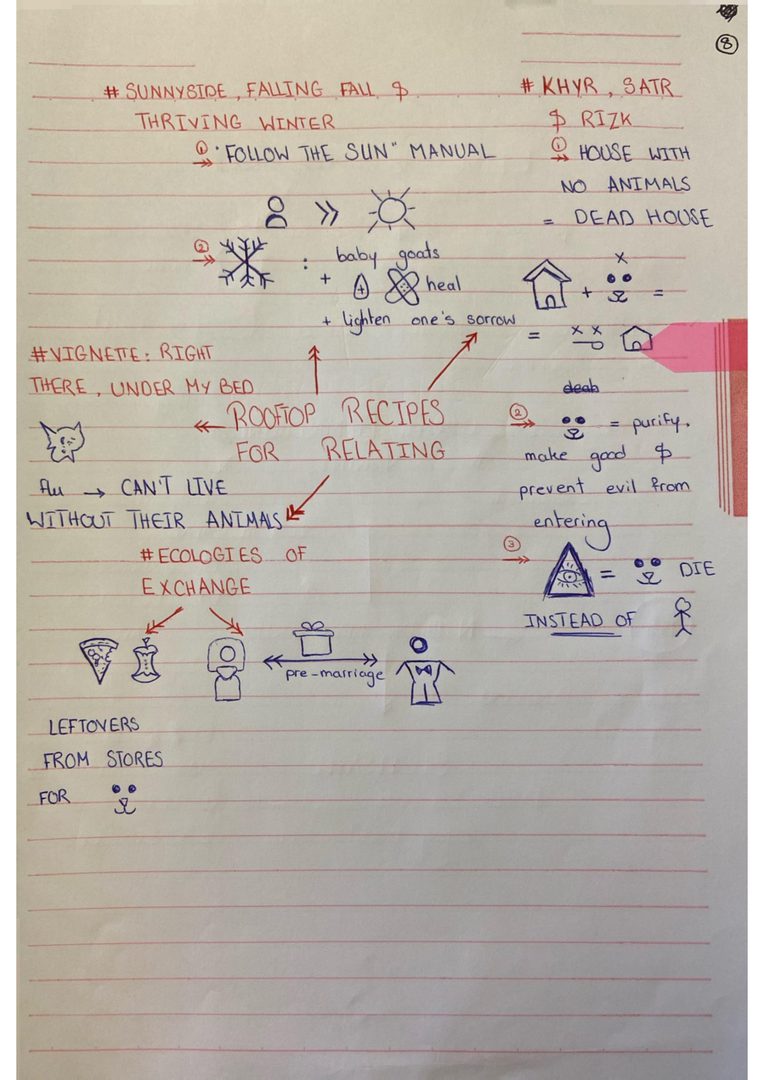

Students were asked to do two things on a weekly basis: if they were not part of the presenting group on Monday, they had to develop icons of use for the discussion. On Thursday everyone brought to class their hand-drawn sketchnotes summarizing the week’s readings. The two combined activities aimed to tackle sketchnoting as both a micro and macro endeavor:

- By developing icons (for example, quick doodles representing “Arab” or “nation”) students built up a vocabulary that would be of recurrence throughout the semester and therefore acquire an ease and familiarity with the process (the more vocabulary you feel comfortable with, the more confident you are at tackling a new sketchnote).

- By summarizing the readings in a one-page sketchnote, students not only put into direct practice the icons they searched for, but they also had to take a step back and think about the overall discussion. Questions to prepare sketchnoted responses included: how do the readings go about arguments similarly/differently, what are the recurrent themes and keywords, and how are they interconnected?

On the first day of class we discussed the syllabus extensively to prepare students to the idea that sketchnoting will be integral to the course (the Thursday sketchnotes represent 20% of the grade). It was always interesting to see how some students were, from the get-go, either excited even if challenged by the idea, or totally alienated and would directly enroll in a different section, never to return.

That first meeting of the semester was designed to ease the fears of many students, such as not knowing how to draw, having no clue what a sketchnote is, or where to start with this weekly endeavor, and to demystify the overall process. I found that after the next session students felt more comfortable with the idea of sketchnoting. For the second meeting, there were no “content driven” assigned readings (nothing related to Arab Society / Kinship in Egypt). Instead, the readings focused on sketchnoting to ease into the practice and alleviate the most immediate anxieties. Students read the entirety of Mike Rohde’s The Sketchnote Handbook (2012) which is written in sketchnotes and therefore makes for a quick and playful reading that directly situates the reader in practice. In addition, a recommended reading included Rohde’s The Sketchnote Workbook (2014) which walks the reader through a variety of uses for sketchnotes in daily life. Rohde’s book is well recognized among sketchnoters, but I also chose it because both the handbook and workbook come with video versions, enabling students from a wide range of learning orientations to opt for whatever option they feel more comfortable with. Finally, I put on Blackboard a “legit procrastination” section with blog posts and quick YouTube videos, all on sketchnoting.

A Lesson in Representation

For anthropologists, but more specifically for multimodal anthropologists working and teaching politics of representation, the sketchnotes offer a unique opportunity to go deeper into the questions of how we see things. Some of the recurring themes or topics across both classes include the representation of Arabs and Muslims. The visual vocabulary needed to draw a summary of our discussions may include any or all of the following: gender, family, society, relationship, Arab, Muslim, Egyptian. When asked to come up with some of those icons during a class session, students would invariably draw “man” as gender neutral (a stick figure) and “woman” as hyper-feminine (long hair, full lips, skirts and dresses). This provided a key opportunity to directly address questions of normativity in gender roles and representations. Another example is the drawing of the word “conservative.” A majority of AUC students identify as Muslims and highlight their international modern subjecthood (as opposed to a supposedly less modern and less international more orthodox majority). The word “conservative” was therefore often drawn with an icon of a woman wearing the veil (hijabi students are a minority on campus and social integration can sometimes be challenging). This too provided a unique opportunity to tie the conversation to our readings on the history, racialization, and global geopolitics of the representation of Muslims in general and Muslim women in particular. It also got us into a conversation on conservatism as a political orientation strengthening the powers in place through the status quo, questioning what, if any, was the role of religion in this context. Finally, when in doubt about how to draw things, I recommended students do what any sketchnoter does, which is to Google-image a term, or to search for it on thenounproject.com, a rich database of icons. This online research itself is a treasure to interrogate universals: how a Muslim is drawn, how family is more often than not a perfectly gendered combination of 4, how Egypt can hardly ever be pictured without pyramids or camels.

How It Went: Things Learned along the Way

As semesters seemed to flash into one another, it was only months later that I began to draw some reflections on things I could have improved in the integration of sketchnotes in the classroom, namely: the lack of sketchnotes-driven assignments, the absence of rubrics, and my own resistance to actually draw alongside students.

Defining what makes a sketchnote “tick”: As I have elaborated above, the weekly focus on sketchnotes aimed to enliven the class participation. This worked fairly well, although some themes (and icons) became quite repetitive in each course as the semesters unfolded. Students were often praising outstanding sketchnotes, which led us to collaboratively, on the board, list what made a good sketchnote: clarity, simplicity, structure, and organization. I did not—but should have—followed up with a handout to be shared early on and collectively modified throughout the semester: while I wanted students to draw their own conclusions on what makes a visual narrative “tick” I think such a handout would have helped the class to have some support material, concrete examples and guides to refer to throughout the semester. This would also have helped both instructor and students with the grading: while I thought that our common deliberations in class and individual orientations during office hours were plenty of guidance, students needed more, and at the end of the semester, students’ sketchnotes that had not evolved or improved got a grade that seemed unfair to some.

Sketchnotes in high-stakes/graded assignments: In a context of heightened economic crisis where an elite education carries heightened financial and social implications, I was very conscious of the impact of grades on students’ anxieties. For that reason I didn’t develop graded assignments that were sketchnoting focused: the assignments’ prompts in both courses were similar to previous semesters (which didn’t include any drawing), and asked students to reflect in writing on a specific topic: no sketching involved, only words. While my goal was to relieve students from the pressure of not being familiar with visual thinking or drawing, this limited the impact of sketchnoting in the classroom: why bother putting all this weekly effort if you are not going to make a proud and shiny use of it in a high stakes moment? Looking back, I could have at least tested the waters by focusing the first assignment on sketchnoting, learning from the experiment, and adapting future assignments and course directions accordingly.

Drawing alongside students: Another mistake was not trying to sketchnote alongside the students myself. Although I did moderate sketchnoting group sessions in class, I never actually took a pen to try my hands at an icon in front of the class because I was just too uncomfortable with it. I worried this would be an opportunity for students to see through me, how inept I am at drawing, and how I am teaching them something I know nothing about. Since I didn’t feel like a true expert on sketchnotes, I did my best to keep my secret impostor identity hidden and performed a polished version of “do as I say, not as I do.” Of course, the vulnerability would surely have brought another layer to the class, and if anything, I could have prepared working on a few key icons before sessions to make myself more comfortable. But I was already way out of my depth during those semesters, teaching what I had no professional expertise in, but also no personal exposure to. Now wasn’t the time to rip through the shreds of authority already coming apart at the seams. This clearly was a mistake though, as I think drawing with students would have shown them that even the most “qualified” instructor has their limits and needs to figure them out on the spot. At the very minimum it would relieve some of our undergrads’ anxieties that they have to leave university with the rest of their lives planned out: if as professors we are still trying to figure things out, there is a reminder there that plans are never set once and for all and are always open to more. In addition, showing that even we, experts in our fields, take the risk to continue to learn, try new methods, and fail along the way, demonstrates how failure can be a generative experience exactly because it doesn’t go as smoothly as planned. Clumsiness here might be the example to lead by.

Regular check-ins on how things went: While my overall goal was to bring fun/play into the classroom and help students “see” in different ways, it was often hard to evaluate whether we had been successful in doing either for lack of regular check-ins on those specific matters. In hindsight, that’s an easy critique to formulate once one is done with constant semester-crisis running mode. When I tried to survey students at the end of each course on what they thought of the sketchnoting experiment, the vast majority was just not interested in the question: it was something they had to do for that class, and so they did it. Those who did answer were very polarized: for a few this was “torture” for they “still didn’t know how to draw.” The blockage was such that no matter how much I tried to alleviate the pressure or remain playful, the students would remain “stuck” and see drawing as an obstacle to their progress. A few commented on how they felt they had to switch their focus to drawing and how that disrupted their learning process, turning content retention into an even more challenging task. On the other hand, the students who had taken up sketchnoting with enthusiasm, even if struggling at the beginning, ended up swearing by it. Some said that they were now using icons as bullet points outside of the course, while for others it helped to “visualize readings in their heads.” Another student mentioned that they exported the method to another social sciences course with a very heavy reading load: “whenever I had to read and memorize points I would draw them so they would stick.” A few commented on the rewarding satisfaction of seeing the finalized page of sketchnotes and finding it actually “impressive.” A passionate student concluded that “the course made me aware of a skill that I did not know I have. I loved this way of taking notes and how it simplified my understanding.”

Concluding Thoughts

Although this was a year during which I wished I had had more time to prepare and improve the integration of sketchnotes in my teaching, I am glad I took the risk to just get started. I am dreaming of one day putting together a short textbook on ethnographic sketchnotes that would offer guidance and prompts for other self-conscious beginners. But in the meantime, I believe this is truly an experience to be repeated and tweaked as one goes. Let me know if you have already or will in the future attempt to bring sketchnotes into your anthropological life. I would love to connect with fellow researchers and educators trying their best pencils and worst talents at it!

Footnotes

[1] It was only much later, of course, that I discovered Doug Neill’s Verbal To Visual “Sketch-Ed Toolkit”: while not primarily designed for college students or humanities/social sciences courses, the toolkit enable the teacher to embed sketchnotes in projects and activities that can be adapted to any level or discipline.

References

Neill, Doug. 2025. “The Sketch-Ed Toolkit.” https://verbaltovisual.com/sketch-ed/

Rohde, Mike. 2012. The Sketchnote Handbook: The Illustrated Guide to Visual Note Taking. Berkeley, Calif.: Peachpit Press.

———. 2014. The Sketchnote Workbook: Advanced Techniques for Taking Visual Notes You Can Use Anywhere. Berkeley, Calif.: Peachpit Press.