We were walking with Juana, an Avá Guaraní teacher from the province of Salta (Argentina), through the school’s courtyard and into the library. Inside was the school director and two elementary level teachers; one of them was Clara, who worked as an intercultural education bilingual assistant. The whole library was wallpapered with colorful posters and books. The walls had high shelves up to the ceiling and everything was covered with books. There was one wall of books that seemed familiar to me. They were school textbooks sent by the provincial government, which I had read online during 2020, the year I could not do fieldwork. I asked Maria if they had used those manuals. She told me that sometimes they used them as reference material for teachers: “Textbooks stay at school, children use them when they come to school. But we do not only use textbooks made by the government. We also use a lot of educational booklets, made by us, because we teach and we know what works. Sometimes you need a snip, not the whole text, and you need only some exercises, not the whole text. Also, to talk about certain topics, it’s good to look at other sources or organize activities where children make their own textbooks. For example, to tell Guaraní myths, it’s a nice activity to tell children to talk to their grandparents and use those stories to write and draw them in other formats.”

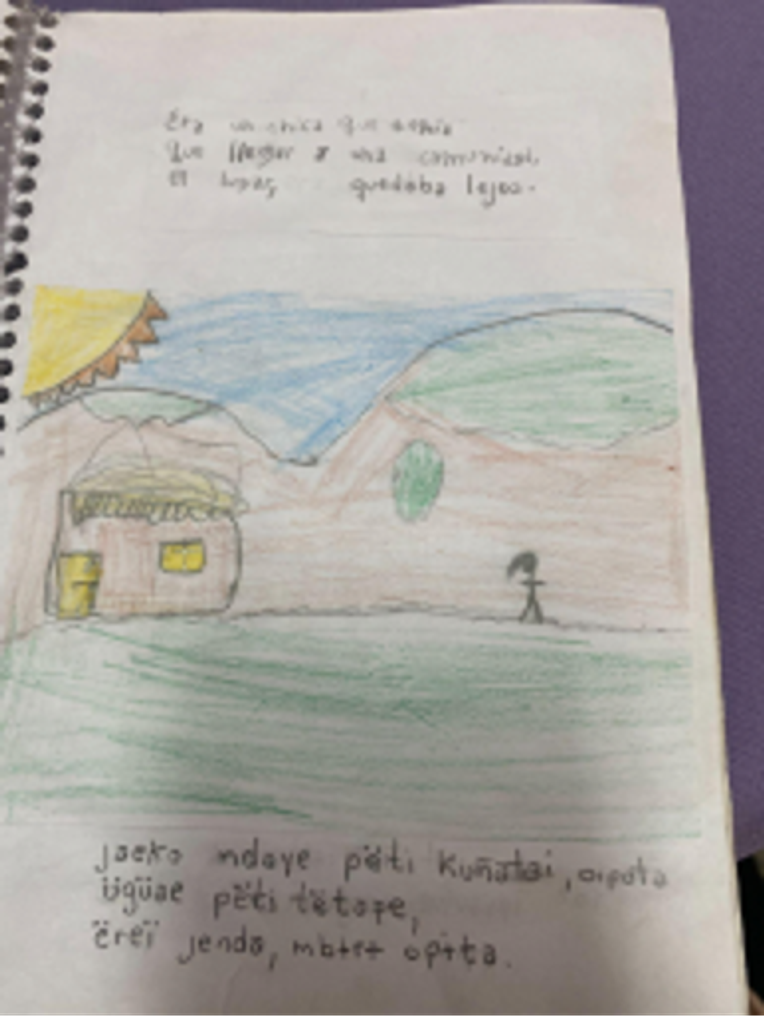

Juana unfolded on the table a series of handbooks with drawings made by students explaining Avá Guaraní myths. While we continued talking, some kids came up and showed me how to read those stories.

Another teacher brought some empanadas (typical food from Salta). We began to talk about which materials they used to teach and we remembered everything that had happened during the COVID-19 interruption of classes. “How tiring! How tiring and exhausting! So much computer and cell phone work!” said Clara, who worked as a teacher in fourth grade.

“We had so much work to do, organizing the meals, completing the education ministry reports… it was really exhausting…. We did so many things to continue teaching to those who did not have cell phones. All kinds of things that were paid from our pocket: designing exercises in .pdf and sending them by WhatsApp, or leaving those booklets in photocopiers for students to print and look them up; charging credits to students’ cell phones who had no way to communicate by cell phone; or visiting students in their communities who could not get to school when this was forbidden to prevent future spread of COVID-19.

While I was talking to the teachers, I remembered a talk I had had a few days ago, where an education official explained to me that the province had distributed thousands of school textbooks to guarantee pedagogical continuity during 2020. I observed the tower of intact manuals in the school library and thought about the value of ethnography and its “being there” mantra, which allowed me to observe how people use educational official textbooks and the number of activities involved in teaching, like handcrafted work. I also thought about those textbooks, which I had read online during 2020, where indigenous peoples were presented as still in the past, static in rural landscapes. In response to an official history that denies them, indigenous teachers developed their own educational materials. But those materials are not available in all schools.

Indigenous People in Argentina

Argentina has one of the largest indigenous populations in Latin America. However, it is often repeated that “Argentines are descended from ships.” From the outside world, Argentina’s population is often confused with the population from Buenos Aires city, which is mostly white, like my colleagues and myself, who have worked several years with indigenous communities. The latest national census indicates that there are fifty-eight native peoples in Argentina, which is equivalent to three percent of the total population. These figures vary significantly according to each province.

In the province of Salta, where I have been doing field research since 2010, fourteen native peoples are officially recognized. They represent ten per cent of the provincial population and their lifestyles are markedly different. In the “highlands” there are Atacama, Kollas, Kollas, Diaguitas/Diaguitas-Calchaquíes, Tastiles, and Lules populations, in what is known as Puna Salteña, a huge area with Inca influence. The lowlands, including areas of Yunga and Chaco, are inhabited by the Wichí, Chorote, Chulupí, Iogys, Weenhayek, Tapiete, Qom (Toba), Avá Guaraní, and Chané peoples. In the recent decades, the expansion of the agricultural frontier related to agribusiness generated the deforestation of large areas of indigenous territories.

Maria belongs to the Avá Guaraní people, one of the largest in the province, who live in the lowlands, in the northeast area, near Chaco and Formosa provinces. This heterogeneity of groups represents a radical diversity, which not only involves different languages, but also profound class disparities and unequal access to services. Many of the indigenous people living in the lowlands have been expelled from their original lands and were forced to migrate to the peri-urban cordons of different cities, while those living in rural communities resist the advance of extractivist fronts.

Argentina has adhered to international legislation recognizing the existence of indigenous peoples and their specific rights, which has made them the recipients of targeted policies. These legislations have been approved in different ways by each province, such as Salta, which has implemented programs in health and education that are named and based on the paradigm of interculturality. One of them is the Intercultural Bilingual Education Program (EIB) (National Law n° 26606 / Provincial Law n° 7546), whose institutionalization process has been quite limited, due to different reasons: scarce training of non-indigenous teaching staff on native peoples, obstacles to indigenous participation, and lack of definition regarding the figure of the indigenous assistant (Hernandez, Szulc, and Leavy 2023).

Juana’s school, located in the municipality of Pichanal (Salta), had a long history of intercultural education. Most of the teachers and directors belong to the Avá Guaraní community and encourage the teaching of the Avá Guaraní language at all school levels. But this wasn’t the situation at all schools.

Ethnographic approaches carried out in different Salta departments allow me to observe that indigenous people had obstacles to access intercultural bilingual education positions in schools. Many teachers, from different educational institutions, told me “here there is no EIB.” After several observations, I find out that in some schools, teachers who were appointed as EIB professors perform “general tasks,” which means that they were assigned to cleaning and/or maintenance of school infrastructure. This kind of practice shows how racism continues despite the implementation of legislation based on special indigenous rights, and that a legal ratification does not automatically translate into guaranteed rights.

This situation shows the value of practicing ethnography: without it, we would be in our desks analyzing technical reports where “EIB teachers” are appointed while in the schools they cannot work as teachers. Visiting schools allows us to see how public policies that seek to guarantee special rights to indigenous people can be used to discriminate against the targeted population. Ethnographic approaches allow us to observe the practices that people do in the name of interculturality. Anyway, how can we contribute, as researchers, to build other interculturality practices? Can we make pedagogic materials from an intercultural perspective? Can we think interculturality beyond “political correctness”? Can we then, from anthropology, do interculturality in another way?

An Intercultural Research Experience

Two years before this field situation described, I began to participate in a project called “Diverse Childhoods and Educational Inequalities in Post-Pandemic Argentina,” funded by the British Academy’s program “Humanities and Social Sciences Tackling Global Challenges.”[1] As a part of research activities, we had read official textbooks, and many others, that were made by official educational organizations to ensure pedagogical continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic. We published a technical report with the analysis, where we pointed out that most of the time, in social sciences sections for elementary school, indigenous people are represented as part of the past.

This analysis was accompanied by fieldwork visits in different provinces of Argentina, carried out by the different researchers who participated in the project. These travels were accompanied by monthly meetings where each one of us reported on the progress of the virtual and face-to-face fieldwork. We asked ourselves how we could generate an instrument that could impact society. These meetings and the discussions that arose were key in the progress of the project. Some of us had more experience in other research lines. For example, I had much more experience in health research and did not know much about education thematics. The meetings were key to defining new objectives and exploring different investigation techniques.

Fieldwork advances had shown us schools’ infrastructure problems and indigenous teachers’ experiences during the pandemic, especially the tasks they had to perform beyond teaching, such as managing food, organizing lunches, and arranging building repairs. We did not yet know what we were going to create as a result from our research, but we did know that we wanted to organize a methodological strategy that would value the work of teachers, which is devalued on a daily basis due to the very low salaries and the stigmatization of the struggle for their rights.

The idea of working around historic event anniversaries came out in collective discussions, because they have a central place in the school calendar in Argentina. That’s how the project “intercultural ephemerides” started to take shape, with a double aim: to recover the indigenous perspective on historical anniversaries and to value indigenous teachers’ work and knowledge in the assembly of didactic materials.

In order to know indigenous perspectives about historic events, we realized that it was necessary to organize a research event to value indigenous knowledge on history and pedagogy, and we had to organize a space and a time where this could be possible. Instead of each one of us returning to each field, we organized a workshop that would constitute a meeting point for all our fields, where these teachers could get to know each other and link with other indigenous teachers. Thus was born the Intercultural Events Workshop, in which for three days, a group of white female researchers from Buenos Aires and one from the United Kingdom shared three days of work with Mbyá Guaraní, Wichí, Chorote, Avá Guaraní, Toba, and Mapuche teachers.[2]

In the workshop, teachers analyzed and criticized a series of worksheets we had previously prepared with didactic resources about a series of historical homeland events that are central in social sciences. In addition, each teacher brought materials they had prepared to work on those anniversaries, which they shared in the workshop space. We organized the time in blocks with a defined duration, in which they first had to work in groups and then share it with the rest of participants. It was very important that the groups were formed by teachers of different ethnicities and that some of the researchers or scholarship holders participated in the groups. At the end of each day, we had a space for sharing everything we had worked on, where we were very careful to give space to all voices in a climate of respect. The different views on certain historical events aroused strong discussions and it was necessary to attend to the plurality of voices and actively seek consensus.

Once the workshop and the leisure activities finished, we continued the meetings and discussions in order to create pedagogical materials that do not reproduce the hegemonic view of indigenous peoples stuck in the past, and could be used in any school of the country, not only the ones that had indigenous students. The result of this different instance of collective work is “Efemérides Interculturales,” a public and free access site, where any teacher from every level or part of the country can access a variety of pedagogic materials to approach historical anniversaries from an intercultural perspective and also to think about the meanings that have historically been forged about indigenous peoples (Leavy et al. 2025).

We hope that materials could be used by anyone who wants to know or to teach about different historical Argentinian events, and we hope that the materials have been able to capture some of the enormous cultural diversity of the native peoples of Argentina, which we tried to capture with the “intercultural” category.

Finally, thinking about the movements implied in ethnography and its permanent reflection about the research process, I would like to point out the value of “being there.” For this project, “being there” involved visiting different schools, talking with public agents, and observing how the act of teaching materializes. It also included listening to Avá Guaraní, Wichí, Chorote, Qom (Toba), Mbyá Guaraní, and Mapuche teachers from different provinces during the workshop. This is useful to think about what we call “interculturalism” in Argentina. In both our fieldwork and workshop, we did not find a singular, unique indigenous perspective. Rather than an encounter or dialogue between two static cultures, we encountered a heterogeneity of views, as well as differences of class, age, gender, and territory, among others.

A long time ago, anthropological studies warned against the limitations of modern states’ proposals on interculturalism in Latin America, which, through a “unitary policy towards indigenous peoples,” have sought to suppress internal differences and define an interlocutor in terms of material lack, while not contemplating the historical and cultural trajectories of each people (Bartolomé 2003, 150). We recover this classic analysis about Argentinian public policies, because it is useful to remember that we have to be careful when we speak about “indigenous perspective” or “indigenous knowledge.” It is not only important to research with others, it is also important to think about what and who are those called “us.” To search for other ways to build intercultural relations between anthropologists and indigenous persons involves considering “the different ways in which, according to our social trajectories, we are all traversed by numerous heterogeneities, including our personal biography, generation and experience with social-historical currents, such as revolution or neoliberalism” (Briones et al., 2016, 73). Following Briones et al. (2016) and Cañuqueo (2018), we warn that those of us who do research must be careful and avoid the use of super categories such as “indigenous knowledge” or “indigenous perspective,” which impede critical perceptions of the processes in which we are all situated.

In memoriam of Clara Josefina Gonzalez

Footnotes

[1] Teachers who participated in the workshop: Piren Ailin Henaiuen, Clara Josefina González, and Celia Millazay Huala (Mapuche teachers from Neuquén); María del Carmen Fernández, Sandra Pisco, and Dora Fernández (Guaraní, Chorote and Wichí from Salta); Cirila Carmelo, Isabel Pereira, and Mabel Carmelo (Qom teachers Chaco); Crispín Benitez and Carina Santa Villalba (Mbyá Guaraní teachers Misiones); and Ema Carolina Gnass (EIB teacher from Misiones).

[2] The project leader was Dr. Lauren Rea (Professor of Latin American Studies, University of Sheffield, UK) and the research team was integrated by Dr. Noelia Enriz, Dr. Ana Carolina Hecht, Dr. Pía Leavy, Dr. Mariana García Palacios, Dr. Andrea Szulc (researchers in National Council of Scientific and Technical Research, Argentina), and Maria Celeste Hernandez (postdoctoral fellow). Also participating as part of collaborator team: PhD Paula Shabel, Soledad Aliata, Luisina Morano, Alfonsina Cantore, and scholarship recipients Melina Varela, Rocío Aveleyra, Hebe Montenegro, Lucía Romano Shanahan and Belén Ibarrola.

References

Bartolomé, Miguel Alberto. 2003. “Los Pobladores del ‘Desierto’ Genocidio, Etnocidio y Etnogénesis en la Argentina.” Cuadernos de Antropología Social no. 17: 163–189.

Briones, Claudia. 2016. “Research through Collaborative Relationships: A Middle Ground for Reciprocal Transformations and Translations?” Collaborative Anthropologies 9, no. 1: 32–39.

Cañuqueo, Lorena. 2018. “Trayectorias, Academia y Activismo Mapuche.” Avá, Dossier: Intelectuales Indígenas y Ciencias Sociales en América Latina, no. 33, 57–69.

Hernández, María Celeste, Andrea Paola Szulc, and Maria Pia Leavy. 2023. Luces y Sombras: La Educación Escolar en Contextos de Interculturalidad de Neuquén y Salta a Partir de la Pandemia de COVID-19.

Leavy, Pía, Ana Carolina Hecht, Mariana García Palacios, Lauren Rea, Andrea Szulc and Noelia Enriz. 2025. “Estrategias Metodológicas Para la Producción Intercultural de los Materiales Educativos ‘Efemérides Interculturales’.” Educación y Ciencia 14, no. 63: 105–123.